Whilst scientific research continues on better understanding the impacts of contrails and other

non-CO₂

effects of aviation, action can be taken now to start reducing these effects. Most importantly, they

must be included in climate legislation if we have any chance of change. The following section looks

at

what can be done at EU level, but global action is needed as well.

I. Development of a strong regulatory framework

Non-CO₂ emissions must be included in EU climate policies and integrated into existing regulations

like

the EU's climate targets, the carbon market for aviation (the EU ETS) and air traffic legislation

(Single European Sky). A clear framework will drive innovation, improve air quality, and support the

shift to net-zero aviation.

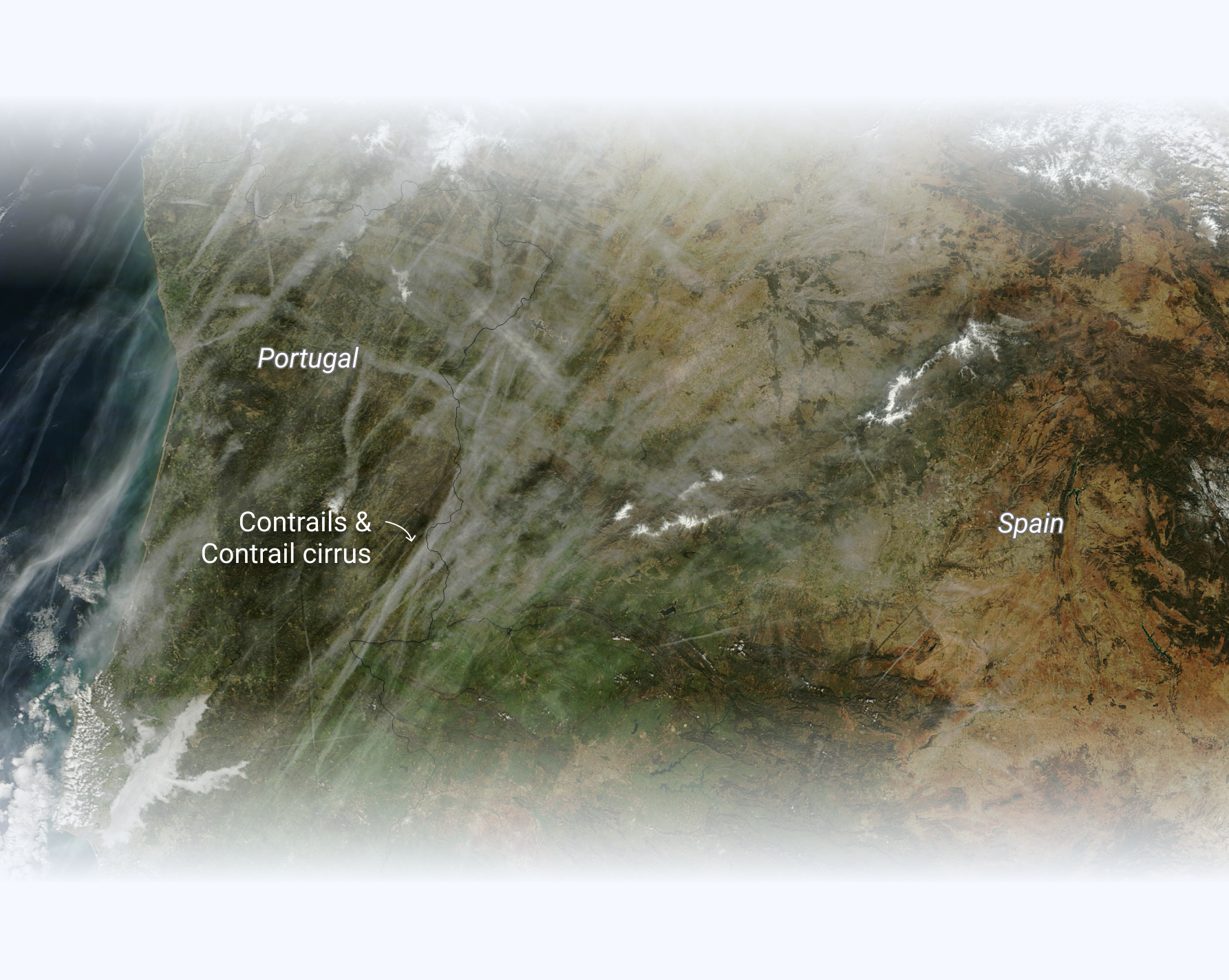

II. Monitoring contrails

In 2025, the EU started monitoring non-CO₂ effects of aviation on intra-EU flights. This is key to

tracking aviation's non-CO₂ impact. Expanding it to cover all flights departing the EU by 2027 - as

originally intended - will improve regulations, scientific models, and international cooperation and

can

serve as a basis for the proposed legislative framework for non-CO₂ emissions.

III. Advancing technology for contrail reduction

Better weather forecasting and humidity sensors on aircraft and satellites are needed to better

predict

and avoid contrails. As technology improves, equipping all aircraft with these tools can become

standard.

IV. Supporting early adopters

EU funding should prioritize airlines and manufacturers adopting contrail avoidance technology,

including satellite monitoring and fleet retrofits. Incentives for airlines performing contrail

avoidance will speed up industry-wide adoption.

V. Boosting transparency for travelers

A Flight Emission Label should include non-CO₂ impacts, helping passengers choose greener flights.

Greater transparency will push airlines to invest in cleaner solutions.

VI. Adjusted air traffic management

Air Navigation Service Providers (ANSPs) are imminent actors in contrail avoidance by allowing

airlines

to do contrail avoidance by adjusting flight planning and rerouting. The EU should integrate non-CO₂

targets into air traffic policies.

VII. Better weather data & coordination

Stronger collaboration between meteorological services and Eurocontrol will improve contrail

forecasting. Standardized EU-wide protocols will help airlines plan cleaner flights.

VIII. Cleaner jet fuels

Low-aromatic, low-sulfur fuels can contribute to the reduction of contrails and air pollution. The

EU

should update outdated fuel standards to promote cleaner alternatives while SAF production scales up

to

realize the benefits already.