In July this year, the European Commission proposed that all new cars would be zero-emission in 2035, to put it on track to meet its Green Deal ambition of net zero by 2050. But setting a goal in itself won’t get Europe to zero. T&E assesses the progress carmakers have made to date in switching to electric and what needs to be done to ensure cars do not contribute to climate catastrophe.

Why do we need 100% zero-emission vehicles sales by 2035?

It’s simple. The average lifetime of a car is around 15 years, so the last conventional car should be sold by 2035 at the latest if we want all cars to be zero emission by mid-century.

Target set, job done?

The EU’s primary tool to make cars cleaner to date has been car CO2 targets for carmakers. The aim is to gradually crank up the restrictions on the amount of carbon emissions a new car can emit, forcing carmakers to produce more zero-emission vehicles. The only viable zero-emission cars at this moment are electric. The technology is available and they are already cheaper to run over their lifetime and will soon be cheaper to buy in every vehicle segment.

Since the introduction of the 2020/21 targets, sales of plug-ins have grown fourfold across Europe, up from 3% in the first half of 2019 to 16% in the first half of 2021. This has reduced average car emissions by nearly one-fifth.

But the electric car boom risks stagnating due to weak intermediate targets between now and 2030, jeopardising the sales of 18 million battery electric vehicles and the resulting 55 million tonnes of emissions savings – more than the annual emissions of all the cars in Spain.

Commitments but no plans

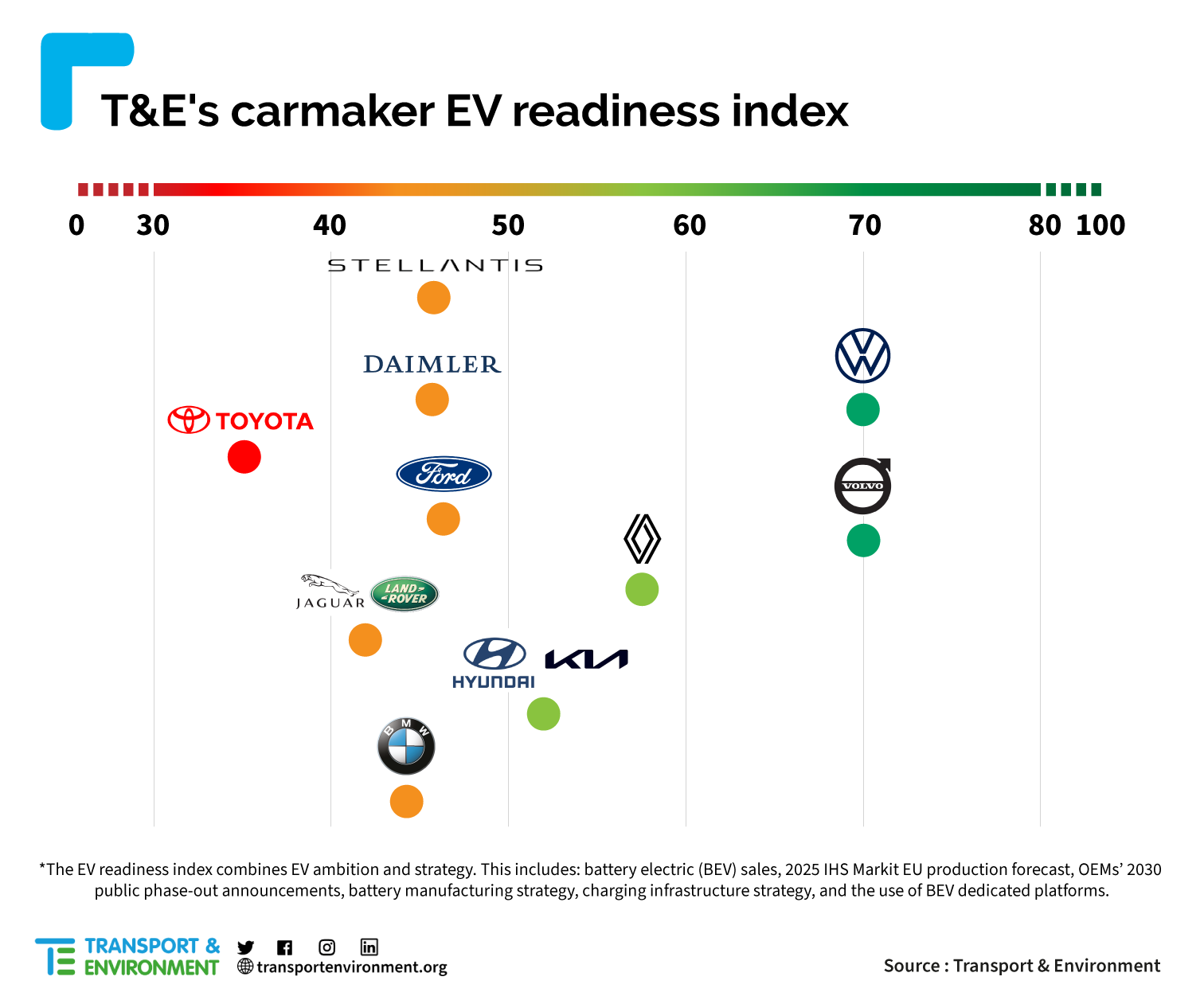

Carmakers themselves have been lining up to show off their green credentials in recent times. But in its assessment of the different carmaker’s commitments and strategies, T&E has found that the majority are way behind where they need to be.

Only Volkswagen and Volvo Cars have aggressive and credible strategies, the analysis found. Others like Ford have an ambitious phase-out target but lack a robust plan to get there. Stellantis, BMW, Jaguar Land Rover, and Toyota ranked worst with low short-term battery electric (BEV) sales, no ambitious phase-out targets, no clear industrial strategy, and an over-reliance in the case of BMW, Daimler and Toyota on hybrids.

Even if their current promises are met, Europe’s sales of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are likely to be at least 10 percentage points lower than they need to be in 2030.

Increasing the car CO2 targets until 2035 is therefore vital if the EU is to ensure that the goal is reached. Leaving it to the carmakers alone is a huge risk bearing in mind their track record in meeting voluntary targets. Analysis by T&E back in 2016, for example, found that carmakers failed on their collective target of selling 3.6% electric cars. They achieved less than half of that.

Without setting more ambitious carmaker targets from 2025 onwards – including an intermediate goal in 2027 and an 80% car CO2 cut in 2030 compared to today – it will be very hard for member states to reach their proposed national climate goals by 2030, T&E’s latest analysis finds. So far from cars being the poster child of decarbonisation as carmakers would like us to believe, they will in fact continue to drag down decarbonisation efforts.

A regulation full of loopholes

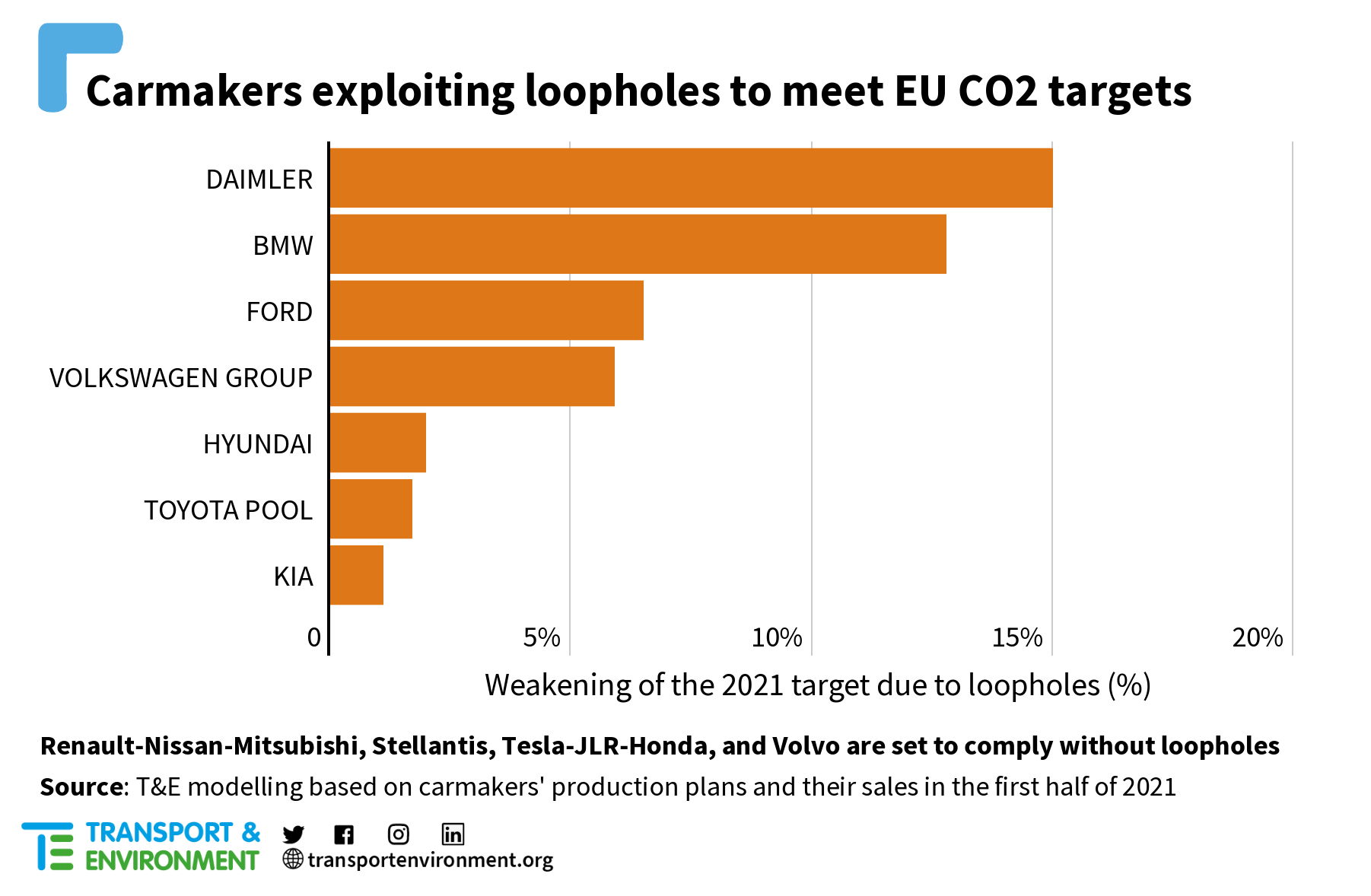

But it is not just weak targets that undermine progress towards electrification. Loopholes in the EU rules let carmakers get away with selling 840,000 fewer fully electric cars this year alone.

Carmakers get easier targets if they sell heavier vehicles, which drives up sales of high-emitting SUVs and plug-in hybrids. Daimler and BMW were especially guilty of exploiting sales of fake ‘electric’ plug-in hybrids, which – when not charged – can actually pollute more than standard cars.

This widespread exploitation of loopholes has helped put all manufacturers on track to comply with EU CO2 targets for 2021. This is despite three companies, JLR, Volvo and Daimler, having higher petrol and diesel car emissions, on average, than five years ago.

Will we go electric on time?

Europe can reach net-zero in 2050, but the evidence suggests that it cannot rely on carmakers to get there themselves. Tighter targets and the removal of loopholes are necessary all the way up to 2035 to ensure carmakers are ready to stop selling petrol and diesel cars after 2035. The technology is there, but can Europe’s politicians deliver?

To see a detailed assessment of each carmakers’ progress, check out T&E’s interactive dashboard.