Italian oil giant Eni is failing to deliver on its promise to produce thousands of tonnes of biofuel crops[1], a new investigation shows. The investigation by Transport & Environment (T&E), in collaboration with The Continent, raises questions over the credibility of the company’s plan – which is backed by Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni – to scale up biofuels as an alternative to oil and gas.

Eni is betting big on biofuels and just recently signed a big deal with Ryanair to supply so-called sustainable aviation fuels. The Italian government for its part is leaning heavily on Eni as part of its foreign policy ambitions to stem migration flows through economic development in Africa. A key part of this strategy is energy investments. At a recent Italy-Africa summit, Ms Meloni spoke of Italy being a natural energy hub between the EU and Africa [2].

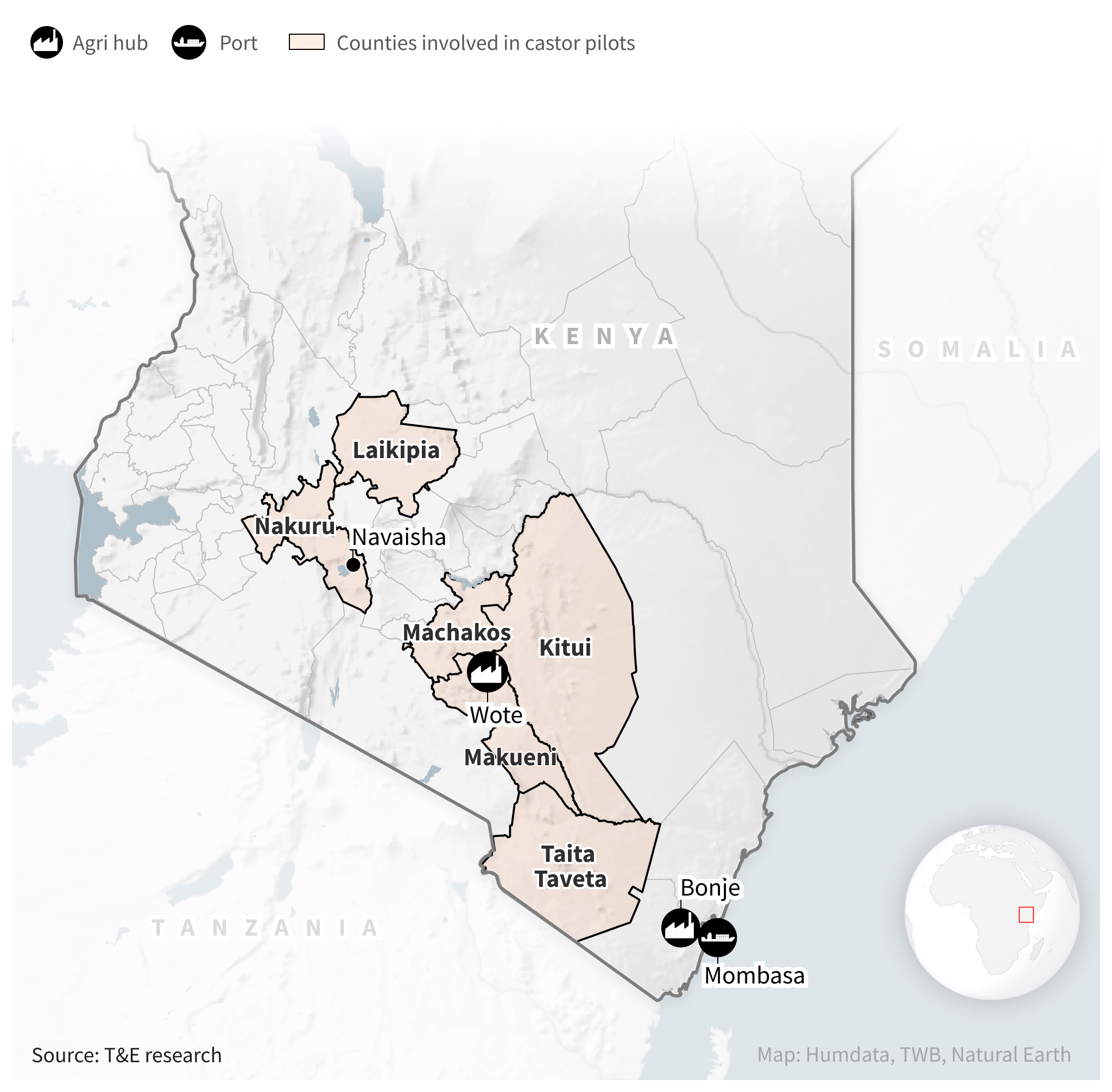

Eni has promised to create an entirely new supply chain of “sustainable oils” from agricultural crops and has set up partnerships with six African countries in order to develop ‘agri-hubs’ that will supply vegetable oil for its refineries. The main crop that Eni is betting on, castor, is advertised as being drought-resistant and suitable for planting on poor quality land. In Kenya alone, Eni aims to enrol 400,000 farmers producing up to 200,000 tonnes a year by 2027.

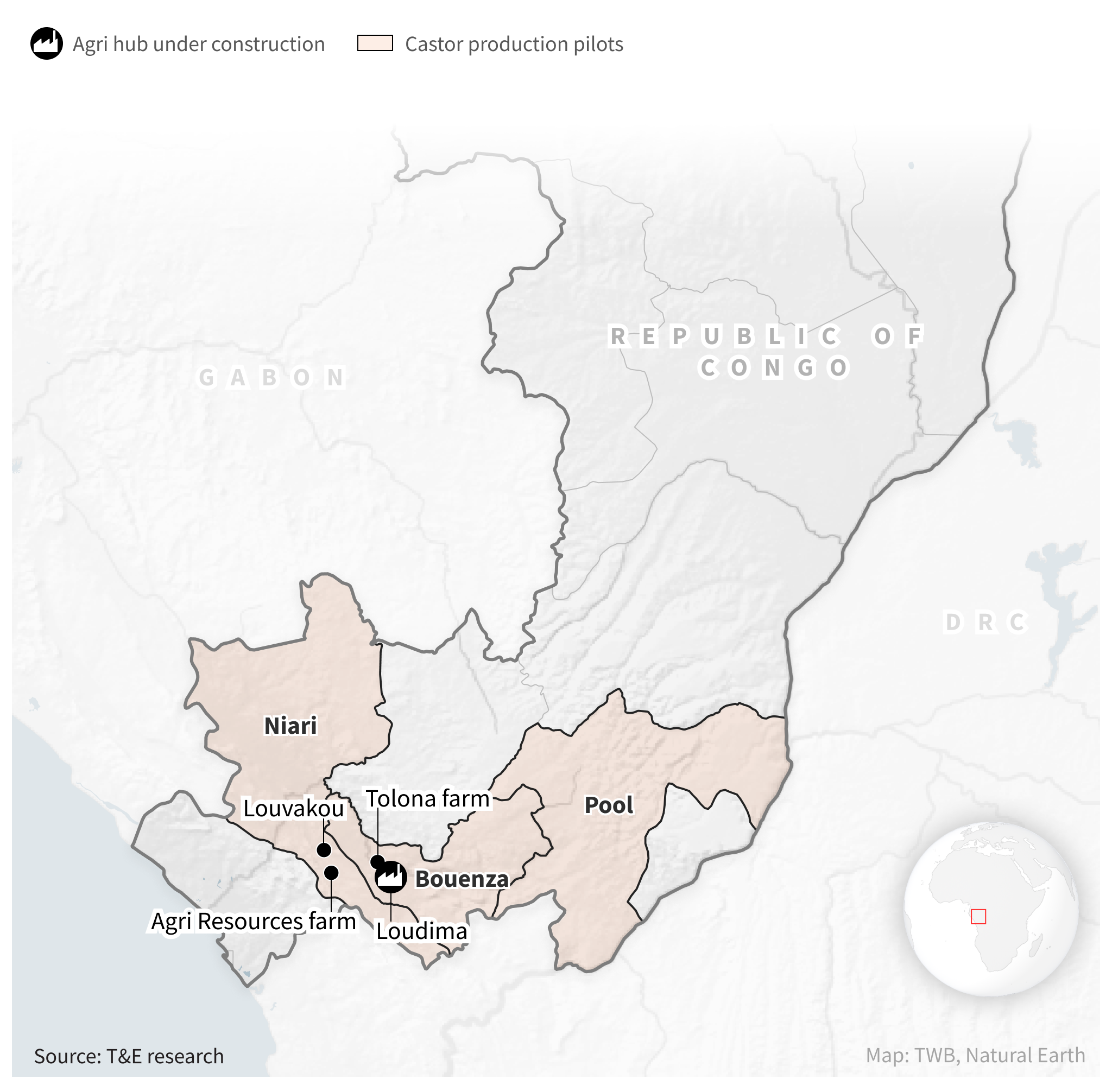

On-the-ground interviews with farmers and other key stakeholders in the two countries where the projects are most advanced – Kenya and the Republic of the Congo – show the company is significantly underproducing. Data analysis in Kenya shows that Eni has failed to reach even a quarter of its 2023 production targets, while, in the Republic of the Congo, Eni’s projects have been languishing at the pilot stage for more than 18 months.

Agathe Bounfour, oil program lead at T&E, said: “This is the first time an oil company has got into the business of farming crops for fuel and represents a major attempt to scale up biofuels production. The evidence from Kenya and the Republic of the Congo suggests that this miracle new energy source being pushed by Eni will not bring development to Africa, nor is it a solution for Europe’s energy needs. Growing drought-resistant energy crops on arid lands sounds too good to be true. That’s because it is.”

Testimonies from Kenyan farmers, gathered by T&E, show that Eni has subcontracted a complex network of brokers and cooperatives, leading to inefficiencies and disappointment for thousands of small-scale farmers who do not receive adequate support or revenue. Additionally, the worst drought in 40 years has severely affected harvests.

In the Republic of the Congo, Eni is taking a different approach. Instead of relying on small-scale farming, it is working with large agribusinesses. But difficulties faced in adapting seed varieties to local conditions mean projects have yet to get off the ground. Local farmers at two of Eni’s pilot sites in Congo also allege that land they traditionally farmed was expropriated by the government in favour of the agribusinesses Eni is working with, Agri Resources and Tolona, casting doubt on the benefits for the local population.

Nevertheless, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which invests public funds on behalf of the World Bank into private sector-led development projects, is considering making a $210m loan to Eni Kenya to develop more agri-hubs in the country. At the time of publication, the IFC told T&E that a decision had not been made yet about the project, but did not provide more details on the specific timeline for the investment decision.

While Eni’s biofuels strategy is struggling, it continues to invest in oil and gas in the region. It has earmarked €25bn to explore and develop new oil and gas projects globally, as well as maintain existing fields. The company has set aside less than €3.4bn for biofuels.

In response to T&E’s questions, Eni denied that it had under-delivered on one of its flagship green projects and emphasised expected “improvements on agricultural yields” with the introduction of new plant varieties.

However, testimonies from project partners and experienced Kenyan agricultural executives raise doubts about whether the introduction of new varieties will be sufficient to address the issues the project has faced up to now.

Notes to editor

[1] Eni’s 2023 agriculture production target for Kenya is 30,000 annual tonnes. Production would rise to 200,000 tonnes per year by 2026, the company said. In the Republic of the Congo, Eni has pledged to produce 170,000 tonnes a year by 2026. Overall, Eni has committed to shipping exponentially increasing tonnages of vegetable oil from abroad to 700,000 tonnes by 2026, or around a quarter of its expanding biorefining capacity.

[2] “Italy’s goal is to help African nations that are interested in producing enough energy to meet their own needs and then exporting the excess to Europe, combining two needs: Africa’s need to develop this production and generate wealth, and Europe’s need to ensure new energy supply routes. Among the initiatives in this area, I would like to mention the one in Kenya dedicated to developing the biofuels supply chain, which aims to involve up to around 400,000 farmers by 2027.”