These are dark and sad days. For Europe, for freedom, for democracy and most importantly for the people of Ukraine. As the world looks on in horror at Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Europe faces its biggest crisis in decades.

As a European federation, we have partners in Ukraine. We offer them our wholehearted support and we stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, and the incredibly brave protesters across Russia who dare challenge Putin and his regime.

The outburst of solidarity and sympathy with Ukraine across much of Europe is heartening. But actions speak louder than words.

Let’s face it: Europe is complicit in Russian aggression. While gas has grabbed the headlines lately, it is our addiction to Russian oil that has helped fuel Putin’s wars, in Georgia, in Ukraine and, let’s not forget, in Syria.

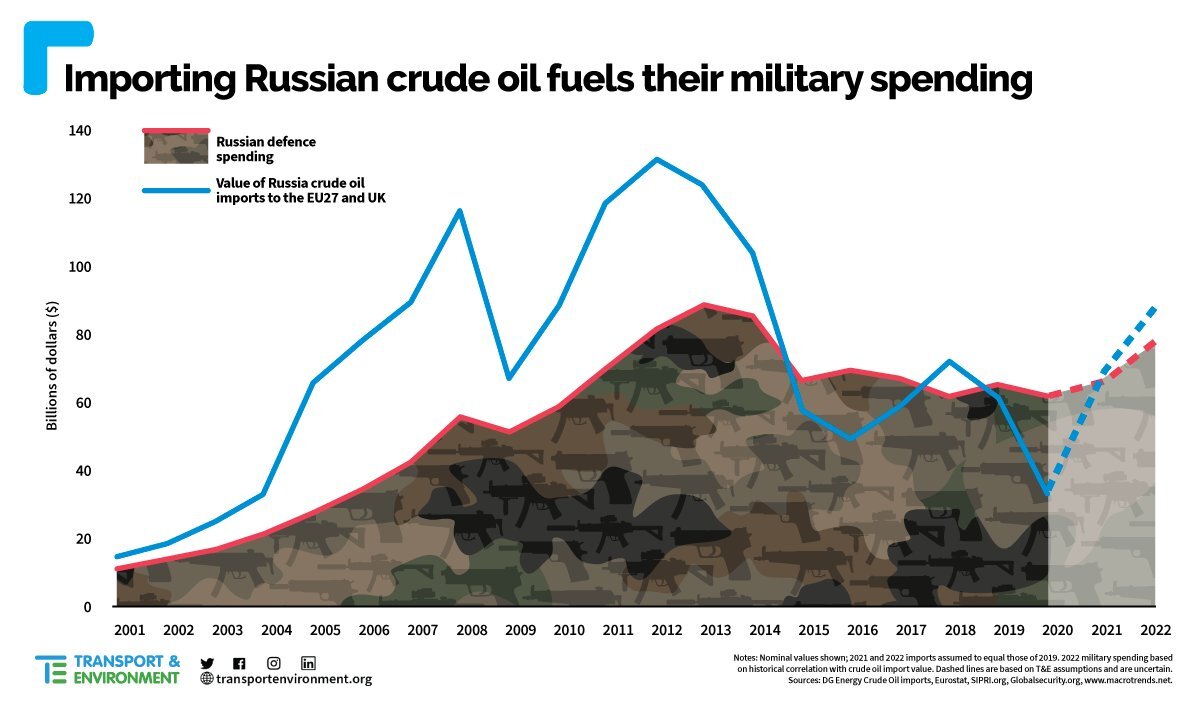

Analysis from T&E shows that as the value of Russia’s crude oil imports to the EU and UK has increased, so has Russian defense spending. There has been a strong correlation for a very long time.

Sanctions on Putin and his cronies are needed. But what good are they if we refuse to tackle the heart of Putin’s regime: Russia’s oil exports? Unless we do that, we aren’t standing with the Ukrainians, we are literally riding with Putin.

Our Ukrainian members are calling for a European embargo on Russian oil and gas and its exclusion from SWIFT. They have a point. Anyone that wants to help Ukraine, should leave their petrol cars at home, and reduce gas heating use as much as possible, at least until Putin has pulled back his army.

And yet, a leaked EU Commission strategy responding to the energy crisis does not even mention oil. Does the Commission not know that oil is a far greater source of revenues for Putin than gas? If we do nothing, Europe will send 80 billion euros to Putin in 2022.

Two-thirds of EU oil is used in transport. In the 1970s energy crisis, governments introduced sweeping plans to preserve energy, including things like car free days and speed limits. Simply stating that the patriotic thing to do is to drive less would be a welcome message. But the Commission should go further. It should set member states a goal of reducing oil and gas usage by several percentage points annually in 2022 and 2023. The hundreds of billions of EU recovery money should be reassigned to achieve that goal.

That’s not what the Commission has in mind, though. Its immediate strategy is mainly about LNG, gas storage and increasing the use of biomethane and hydrogen. It’s a flawed strategy that looks like a copy paste of the 2014-15 EU energy strategy which did nothing to prevent higher oil and gas demand as well as higher dependence on Russia.

The EU Green Deal includes much better recipes: efficiency, renewables and electrification. Freedom energy as Germany’s Finance Minister calls it. But the EU plan has one fundamental weakness. It has practically no effect before 2030. Unless we change that, oil and gas demand will remain flat or rise as restrictions ease. In other words, we continue to ride with Putin.

Faced with the biggest war in Europe since 1945 and the prospect of new military adventures in EU states – perhaps not right now, but what if Trump returns – we expect the Commission to propose a serious plan to address our oil dependence on Russia. Else, we remain complicit in Putin’s wars abroad and repression at home.

If you would like to support humanitarian assistance in Ukraine, please consider giving to one of the following organisations: