In transport, as in other areas of the economy, taxation is one of the most important tools to generate behavioral change and plays an important role in the transition to electric cars in Europe. Whilst countries like Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway have long adopted smart taxation policies that have resulted in high battery electric vehicle (BEV) uptake in their countries, others like Bulgaria and Cyprus do very little to penalize polluting cars.

Leaders and laggards: applying the ‘polluter pays’ principle to cars

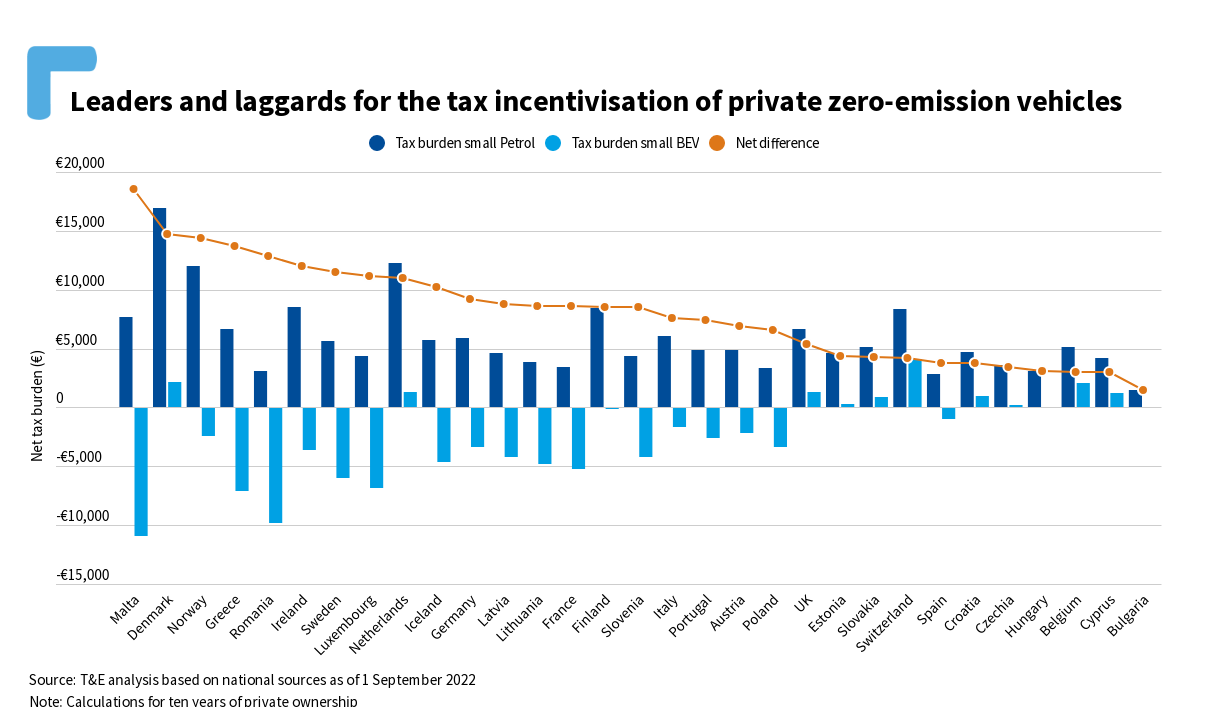

For private cars, governments should apply taxation according to the ‘polluters pay’ principle, whilst simultaneously introducing strong incentives for BEVs. Too few European countries apply this model, resulting in a great variety of tax burdens of a typical car. For a small petrol car with ten years of private ownership, the tax burden ranges from €1,500 in Bulgaria to €17,000 in Denmark. Tax burdens on polluting vehicles are very high in Greece and Romania for their region (see graph below).

In this early phase of the transition, a high tax burden on polluting cars should be combined with low taxes on zero-emission vehicles, T&E says. The result is tax differential, which serves as a good metric to compare car taxation across European countries. The tax differential for a typical BEV is often correlated with the uptake of these cars at the country level. For a small car, the highest tax differentials are found in Malta, Denmark, and Norway while the lowest tax differentials are in Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Belgium.

The range of tax differentials are explained by good and bad practices of taxation. Ten countries do not have a car tax (i.e. acquisition or ownership) on CO2 emissions. These include Poland, Czechia and Estonia. Nine countries – counting Germany, Switzerland and Romania – do not have an acquisition tax (despite its influence on new purchases) and four countries do not have an ownership tax. These include the suspected laggards, Poland and Czechia.

On the other hand, purchase grants for low and zero-emission vehicles have helped accelerate the uptake of BEVs in Europe, and are found in 23 of the 31 countries. Malta has the highest purchase grant in Europe for zero-emission vehicles (€11,000) and Romania the second highest (€10,200). France, Italy, and Romania are the only countries which still have purchase grants for conventional ICE vehicles.

Griffin Carpenter, company cars analyst at T&E, said: “In the midst of a climate and energy crisis, taxpayers across Europe are effectively subsidizing the pollution of cars. Too many countries suffer from outdated systems, absence of taxes and lack of incentivisation for zero-emission transition. Let’s turn this around quickly, help households buy EVs and clean our air, all at once.”

Taxation of corporate fleets: the low-hanging fruit in the decarbonisation of road transport

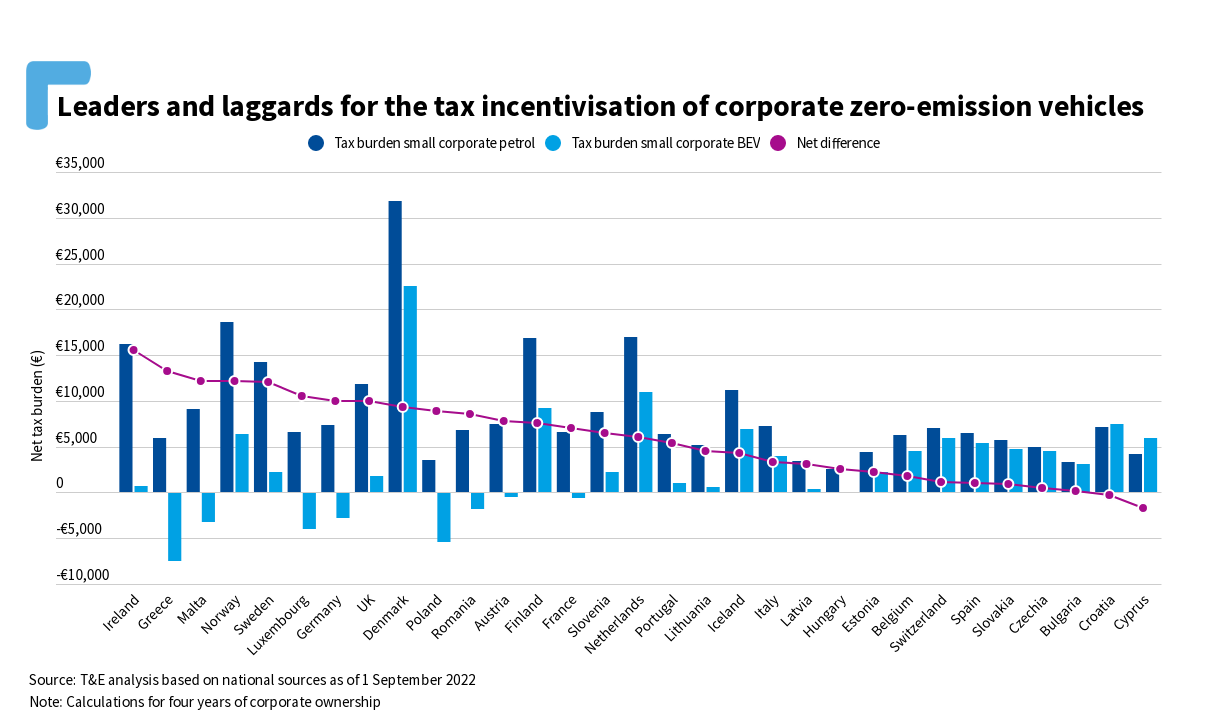

As company cars account for over half of new cars sold every year and are responsible for 73% of new-car emissions in Europe, smart taxation policies that result in high BEV uptake in the corporate channel are more necessary than ever. This is most often achieved through Benefit-in-Kind (BiK) schemes. When an employer provides a company car to an employee, and this car is used for private purposes by the employee, a taxable BiK arises. Higher BIK on polluting cars means more punitive taxation.

In countries like the UK or Norway, the company car tax regime has been incredibly beneficial for the uptake of BEVs for corporate buyers. The UK applies a BIK rate that linearly increases based on car emissions – a system unique in Europe that has proven very successful. BiK rates in Norway for polluting company cars are relatively high compared to other European countries with a rate of 30% of car value up to €32.960. In France and Germany, on the other hand, benefit-in-kind rates are too low, with no incentives for BEVs. As a result, electrification rates in the private channel are twice as fast as those of the corporate channel in Europe’s two largest car markets.

“Company cars pollute more because they are driven more. But governments are hampering the transition to clean fleets by continuing to offer low tax regimes for polluting cars. Incentives for corporate BEVs is the low-hanging fruit of car taxation and the decarbonisation of the whole fleet”, concluded Griffin Carpenter.

Using The Good Tax Guide

Based on learnings from the country comparisons and research on taxation, twenty principles of environmental taxation are developed in The Good Tax Guide. For more detailed analysis on car taxation in the largest European car markets, please consult:

- UK: Car taxation in the UK benefits company car drivers more than households for EV purchases

- France: Fiscalité automobile en France : la majeure partie des voitures polluantes sont exonérées du principe du pollueur-payeur

- Germany: Nur Bonus, kein Malus: Deutschlands niedrige Kfz-Steuer hält die Vorherrschaft umweltschädlicher Autos aufrecht

- Spain: Fiscalidad de los vehículos en España o donde quien contamina no paga

- Italy: Auto: In Italia le politiche fiscali frenano la crescita delle elettriche

- Poland: Boom na rejestrację samochodów luksusowych w Polsce przez system podatkowy, który faworyzuje samochody zanieczyszczające środowisko