While investors have poured billions into the battery industry, and Europe is set to have enough batteries to power over 90% of all new vehicle sales by 2030, a slowdown in electric vehicle sales would jeopardise Europe’s chance of becoming the global leader in one of the twenty-first century’s key technologies.

Europe’s surging EV market has resulted in plans for 38 battery gigafactories, totalling over 1000gWh of output and almost €40bn in investment. Yet, weak CO2 standards between 2022 and 2029 give carmakers little incentive to increase the sales of electric cars until 2030. This will result in well over half of the expected output having no market. This is a missed opportunity to boost Europe’s economy and secure thousands of skilled jobs, says T&E.

Julia Poliscanova, senior director for vehicles and emobility at T&E, said: “The battery industry is successfully responding to Europe’s e-mobility ambitions, yet EU policy-makers are failing to provide regulatory certainty and guarantee an adequate market for electric vehicles. The EU and UK must raise CO2 standards throughout the decade to avoid wasting billions of investments and derailing the battery boom.”

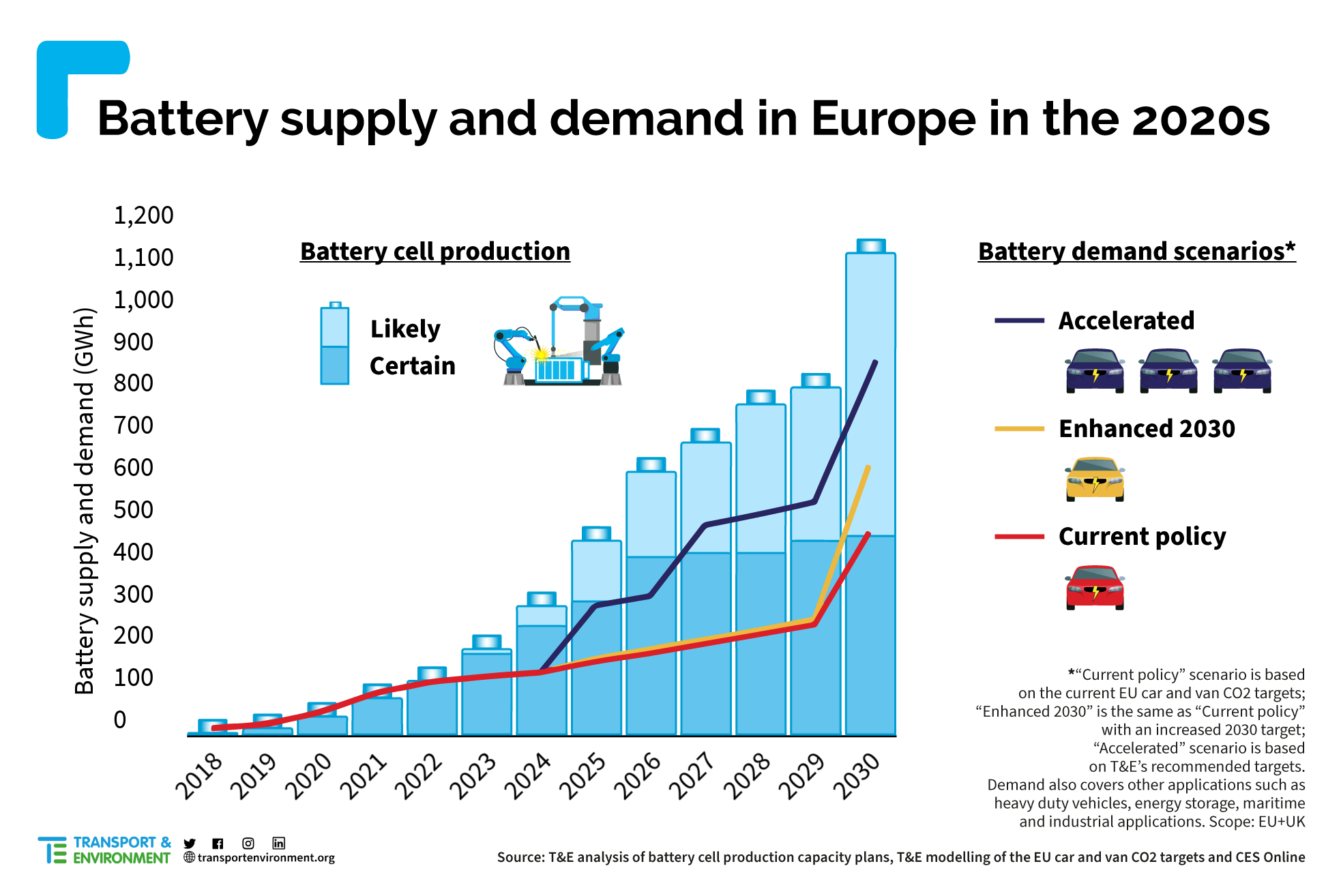

Planned battery production could be almost three times higher than the minimum demand in 2025-2030, according to analysis by T&E. Under current regulations, battery demand will be a mere 174 GWh in 2025, rising to 485 GWh in 2030, when a more ambitious CO2 standard finally enters into force. This is far below the anticipated 462 GWh of battery capacity by 2025, growing to 1,144 GWh by 2030. Much of the excess battery supply can be solved by raising the 2025 CO2 reduction target to 25% and setting an additional target of -40% for 2027, says T&E.

To date, 17 of the 38 planned gigafactories have secured full funding, worth €25.5bn. A further 10 projects have secured partial financing, including many that are key to Europe’s domestic battery autonomy such as Britishvolt in the UK, Italvolt in Italy, Freyr in Norway, and Basquevolt-Nabatt in Spain. An additional 11 projects – including Volkswagen’s four gigafactories – have recently been announced but no data are yet available. Higher CO2 targets would directly benefit the newer wave of predominantly European battery projects.

Julia Poliscanova added: “While higher targets would secure investments today, achieving and maintaining global leadership is much bigger than this. Battery manufacturing is the most valuable part of the EV supply chain and with China and the US also pumping huge amounts of cash into battery making, Europe’s wasted investments this decade will be nothing compared to the opportunity missed this century.”

The EU is expected to propose new car and van CO2 targets in July. T&E recommends that the EU increases the 2025 target and sets an additional binding target for 2027. All petrol and diesel cars engines should be phased out by 2035 at the latest, says the group.