New cars in Europe are getting 1 cm wider every two years, on average. That’s according to research by Transport & Environment (T&E) which says the trend will continue due to the rising sales of SUVs – unless lawmakers take action. Around half of new cars sold are already too wide for the minimum on-street parking space in many countries. Paris could be the first major European capital to tackle this trend if citizens endorse higher parking charges for SUVs in a referendum next month.

The average width of new cars expanded to 180.3 cm in the first half of 2023, up from 177.8 cm in 2018, the T&E research finds.[1] Data compiled by the ICCT confirms the same trend in the two decades up to 2020.[2] New cars in the EU are subject to the same maximum width, 255 cm, as buses and trucks. T&E said that unless the EU width limit for cars is reviewed and cities impose higher parking charges, large SUVs and pick-ups will continue to expand to the cap meant for trucks.

James Nix, Vehicles Policy Manager at T&E, said: “Cars have been getting wider for decades and that trend will continue until we set a stricter limit. Currently the law allows new cars to be as wide as trucks. The result has been big SUVs and American style pick-up trucks parking on our footpaths and endangering pedestrians, cyclists and everyone else on the road.”

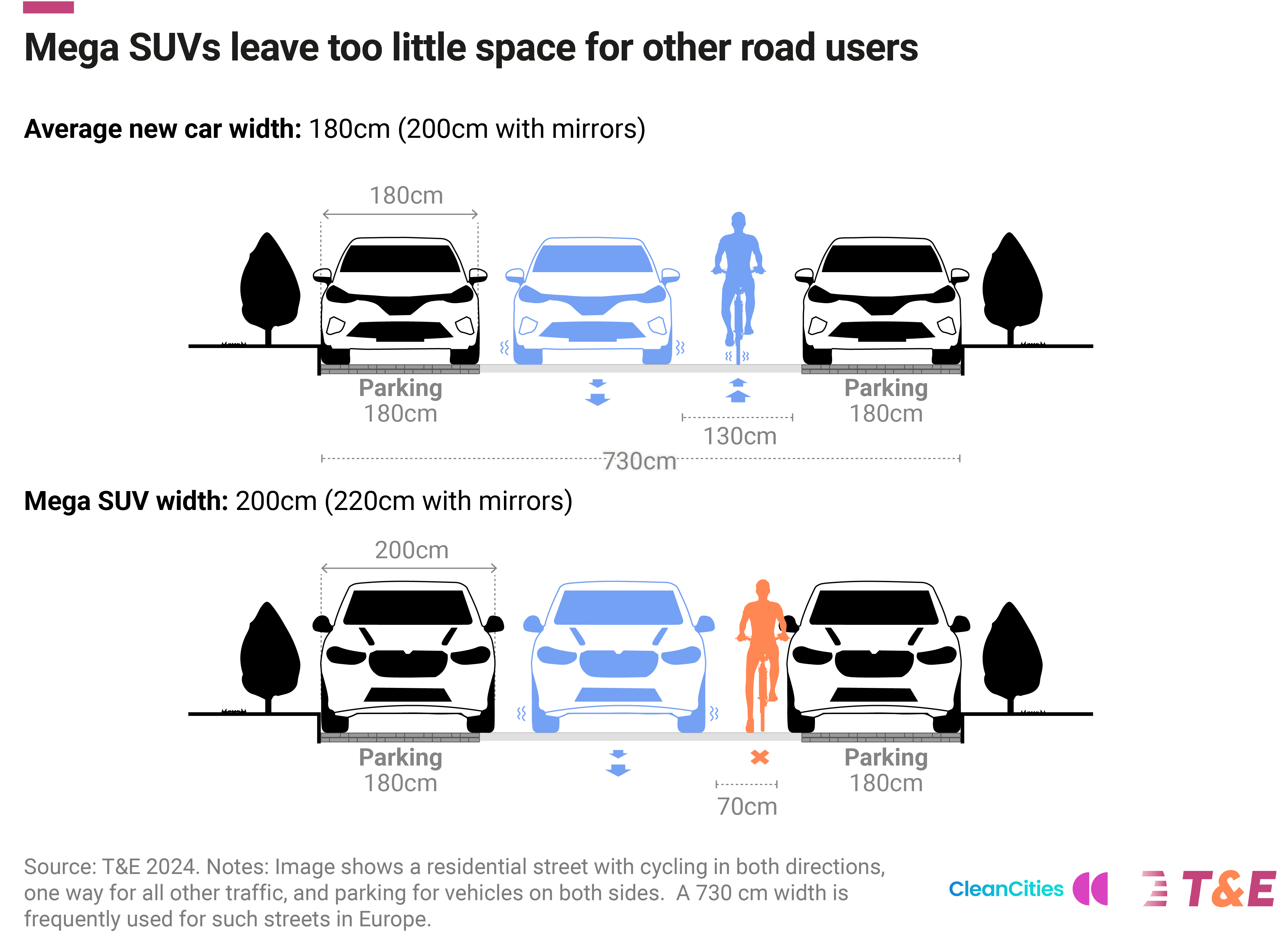

Among the top 100 models in 2023, 52% of vehicles sold were too wide for the minimum specified on-street parking space (180 cm) in major cities, including London, Paris and Rome, the research also finds. Off-street parking is now a tight squeeze even for the average new car (180 cm wide), while large luxury SUVs no longer fit. Measuring around 200 cm wide, large luxury SUVs leave too little space for car occupants to get in and out of vehicles in typical off-street spaces (240 cm).

The growth in size is very pronounced among large luxury SUVs: in the most egregious cases, the Land Rover Defender grew by 20.6 cm and the Mercedes X5 by 6 cm in just six years. In 2023, Volvo went 4.1 cm wider with its EX90. Carmakers are using this growth of the largest SUVs to also increase the width of vehicles in the midsize and compact segments.

The trend towards wider vehicles is reducing the road space available for other vehicles and cyclists while parked cars are further encroaching on footpaths. The wider designs have also enabled the height of vehicles to be further raised, despite crash data showing a 10 cm increase in the height of vehicle fronts carries a 30% higher risk of fatalities in collisions with pedestrians and cyclists.[3]

Several European cities have already introduced more restrictive parking rules for SUVs.[4] The city of Paris is the latest and largest European city to tackle the trend of larger cars and has called citizens to vote on whether parking fees should be tripled for particularly heavy cars. A recent poll by the Clean Cities Campaign found that around two thirds of Parisians are in favour of higher parking fees for large, heavy and polluting vehicles.[5] If approved, new measures in the French capital would set an important precedent for many other European cities that are considering similar changes.

Barbara Stoll, Director of the Clean Cities Campaign, said: “Monster SUVs are a threat to the urban fabric of our cities. Unless we act now, more and more of our precious public space will be taken away from people by ever larger cars – this is not the cleaner, brighter and greener future that citizens want. On 4 February, Parisians have a unique opportunity to lead the way and say no to these polluting and dangerous giants taking over our streets.”

T&E said EU lawmakers should mandate a review of the maximum width of new cars when they update the legislation in the coming months.[6] Also, city authorities should set parking charges and tolls based on vehicle size and weight, so that large luxury SUVs and pick-ups pay more for using more space.

Read more:

Briefing: Ever-wider: why large SUVs don’t fit, and what to do about it

Notes to editors:

[1] T&E compared the top 100 cars sold in 2018 to the top 100 in the first half of 2023.

[2] Average car width in the EU increased from 170.5 cm in 2001 to 180.2 cm in 2020. The International Council on Clean Transportation, European vehicle market statistics – Pocketbook 2021/22. Link.

[3] VIAS Institute (2023). Des voitures plus lourdes, plus hautes et plus puissantes pour une sécurité routière à deux vitesses ?Link. The 30% increase is based on vehicle fronts 90 cm high compared to 80 cm.

[4] The city of Lyon recently adopted higher parking costs for heavier vehicles, requiring SUVs to pay €15 more per month than an average car and €30 more than electric vehicles. Tübingen, Germany, has been applying a 50% mark-up on residential park charges since 2022. The association of German cities came out in support of higher parking charges based on the size of the vehicle.

[5] On February 4 2024, Paris is set to hold a referendum in which residents will be asked to vote on setting a specific parking tariff for heavy cars. The new rules would triple the price of parking (to €18 per hour in central districts, and €12 in other areas) but would not apply to Paris residents’ parking. The city organised a similar vote last year on the prohibition of shared electric scooters, following which it became the first European capital to impose such a ban. A survey for Clean Cities and Respire carried out by OpinionWay in January 2024 revealed that 61% of Parisians support the implementation of parking pricing by weight, a figure which rises to 70% if this measure is applied under conditions (revenues reinvested in the improvement of mobility in Paris, application to non-residential parking only, etc.).

[6] In the week of 12 February, the EU Parliament’s transport committee is expected to vote on an amendment to the Weights and Dimensions Directive that would mandate a review of the maximum width for new cars. The review clause would not specify new limits but would require the EU Commission to examine the issue. Page 145. Link.