Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

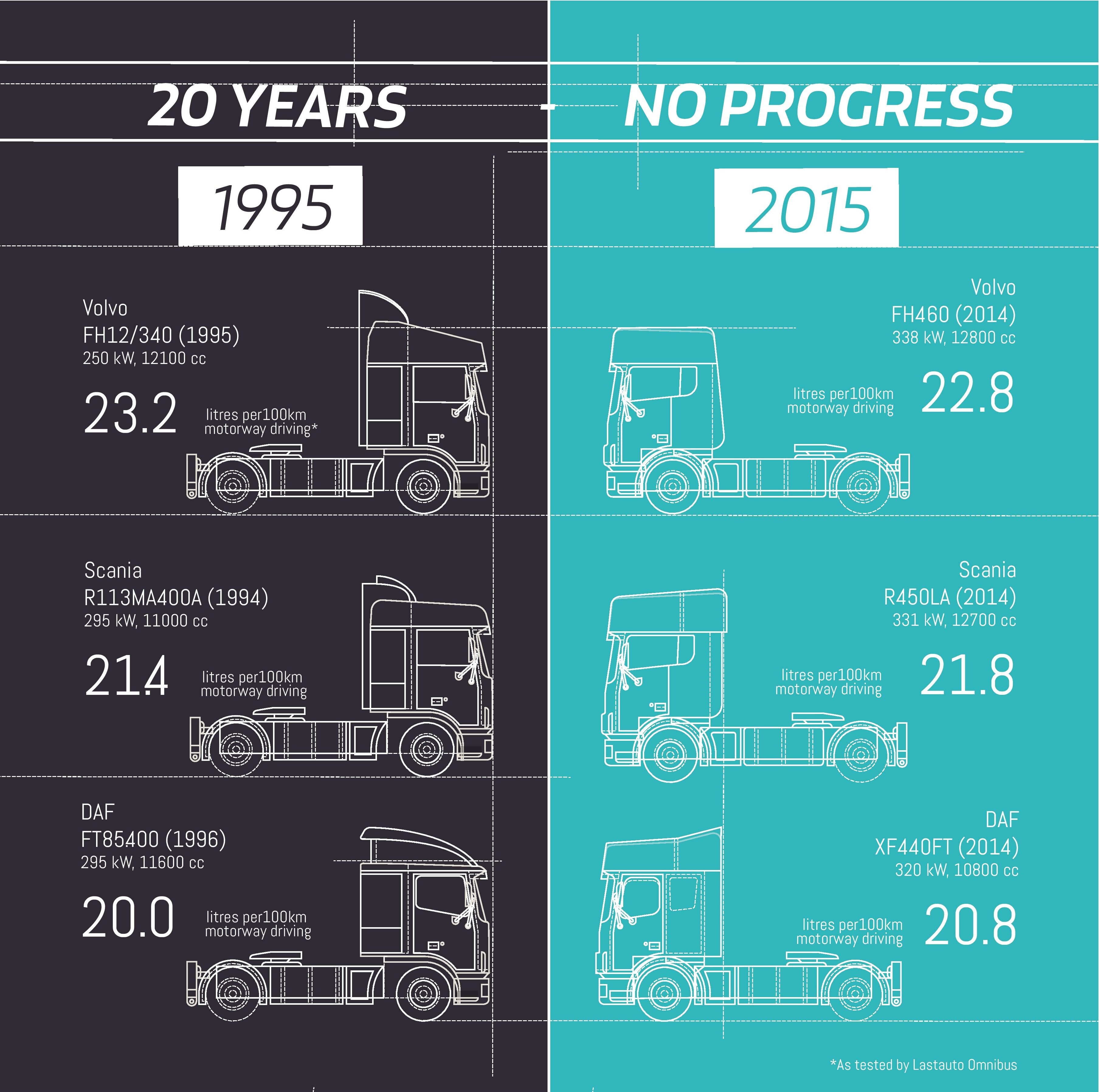

For the non-truck geeks, the background to this is that for quite some time, NGOs and researchers (but ACEA and Shell too) have used the Lastauto Omnibus testing data to show that truck fuel economy has mostly stagnated from the mid-1990s onwards. That lack of clear progress was one of many arguments – probably not the decisive one – which convinced the European Commission that the time had come to introduce truck CO2 standards.

A few months ago we took some vehicle pairs out of the Lastauto testing data to illustrate the lack of progress for a few truck brands – a full methodological note on how we did that can be found here. Last week we did the same but in real life (see pictures here) at the entrance of the European Parliament, under the slogan ‘Trucks are stuck. Make them move’.

The truck industry wasn’t too happy about this and so Mercedes commissioned Lastauto Omnibus to test three Mercedes vehicles. The objective: to compare how their fuel economy had improved over the last 20 years.

And guess what? The Mercedes test shows a 22% improvement between 1996 and 2016.

Cherry picking your way to excellence

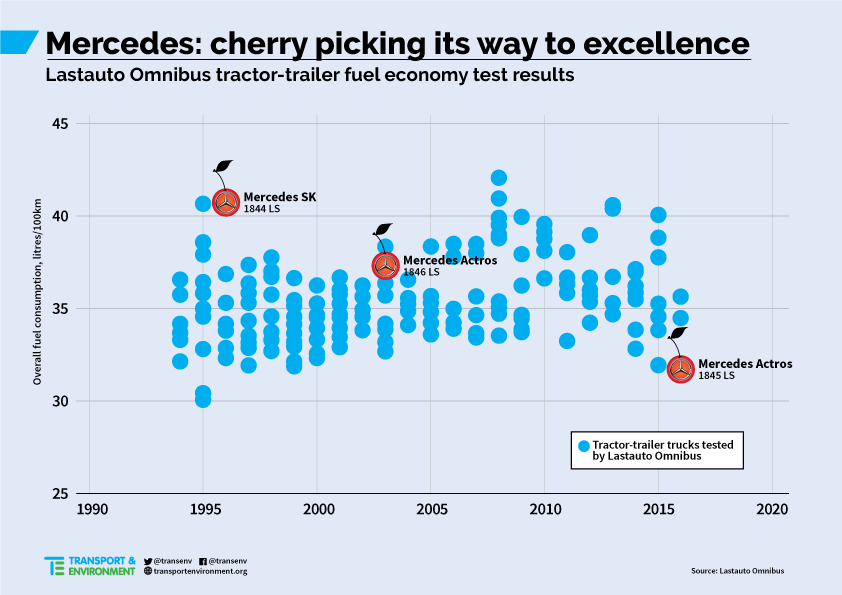

So we are saying there hasn’t been much progress on fuel economy, Mercedes says they’ve made spectacular progress and we’re both using the same testing organisation. How is that possible? Quite simply, it matters a lot which points – in this case which trucks – you’re comparing.

We didn’t really get to choose the vehicles. We had at our disposal a database containing all trucks selected and tested by Lastauto Omnibus until roughly 2014. We selected pairs with the help of experts (see for above note for how we did this). In the case of the Mercedes test, it was the truckmaker that selected and supplied the trucks for the test. So unsurprisingly it supplied the magazine with a bad 1996 truck and an excellent 2016 one.

The 1996 SK 1844 LS was at the time – according to Daimler – Europe’s most powerful truck. It is equipped with an enormous V8 engine (14.6 litres swept volume, for the geeks) and, according to Lastauto’s test, it guzzles 40.8 litres of diesel per 100km. As you can see below, this is greater consumption than any of the trucks that Lastauto tested in the 1995-2000 period. Even if you factor in that the new Lastauto cycle (since 2010) is a bit more demanding, the 1996 truck would still be an outlier.

The 2016 Mercedes Actros 1845 LS has a more representative engine. It also performs very well. In fact, it’s one of the best performing vehicles in the entire database. That might be because 2016 models are actually better performing – and there’s some indication they are – but also because the truck has a number of fuel-saving options (for example, an aerodynamically optimised StreamSpace cab, predictive cruise control). That means it is probably better – and more expensive – than the standard vehicle most operators buy.

If you dig a little deeper you see that Mercedes has selected three vehicles with comparable engine power. This is an important choice which contrasts with what we have done. In our vehicle-to-vehicle comparison we chose to compare vehicles with a comparable engine size (around 11,000-12,000cc) which is what is typically used in long-haul operations. Over the past 20 years, engine power for similar engine size, has increased significantly and has eaten away some of the engine efficiency improvements. That means today’s trucks have far better performance (in addition to much reduced pollutant emissions) but not necessarily far better fuel consumption. We chose to factor that into our comparison; Mercedes didn’t.

So in a nutshell, Mercedes has spent a lot of time (and money?) proving its best 2016 truck is better than a bad 1996 truck. In Shania Twain’s words: “that don’t impress me much”.

The good news here?

Clearly our truckmakers are very capable. And clearly, there is further technological potential to improve truck fuel economy. The cooperation between Mercedes and Krone – delivering a 20% more fuel-efficient tractor-trailer combination – only serves to illustrate this. In fact, the Commission and the ICCT estimate a 2015 base truck could become 35–40% more fuel efficient by 2030 without increasing costs for users. The whole point of CO2 standards – which we campaign for – is to make sure all of this off-the-shelf technology becomes “standard” and affordable for all companies much more quickly.

To get the best possible standards, we’d ideally have OEMs cooperating with regulators. That’s what happened in the US: Mercedes, Volvo, Paccar (DAF) and Navistar (VW) worked with the US EPA to develop post-2020 CO2 limits. When the truck rule was adopted Mercedes, Volvo – and fleets too by the way – welcomed it. In Europe, Mercedes and co. are busy trying to stop, or at least delay, CO2 standards. The flawed Mercedes test is part of that campaign.

Which makes me wonder, why can’t our automotive industry be as constructive at home as it is abroad?