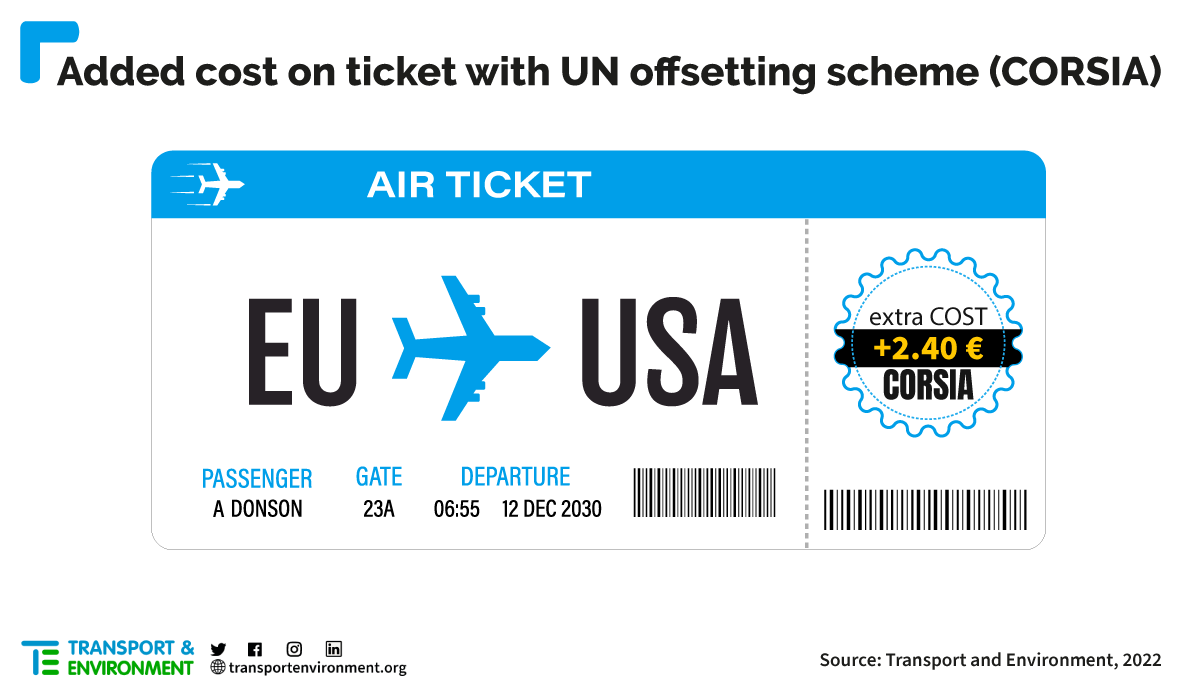

ICAO, the UN body tasked with cutting global aircraft emissions, uses a system of purchasing emissions offsets that has so far proven totally ineffective for reducing aviation’s climate impact. New analysis by T&E shows that on a flight from Europe to the United States, on average passengers would have to pay as little as €2.40 to offset their carbon emissions in 2030[2]. On a flight to the Middle East, the added cost per passenger would be €1.40; to China, a mere €3.5. Such amounts are inadequate when considering the cost of decarbonising the aviation industry, T&E says.

The total cost for all airlines operating flights from the European Economic Area (EEA) to the US to offset their emissions under the UN scheme CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation) are expected to be €118 million in 2030, representing only 0.4% of their total operating costs in 2030. For those carriers operating flights from the EEA to the Middle East, purchasing offsets would cost €40.3 million in 2030 – a figure representing just 0.3% of total operating costs.

Jo Dardenne, aviation director at T&E, says: “Offsetting is a climate fraud, perpetuated on unsuspecting passengers by an industry resisting real climate action. Paying €2 to fly ‘guilt-free’ to New York is a climate absurdity. Having transport ministries continue to come to the negotiating table with offsetting as their golden solution is unacceptable. CORSIA is a non-starter for our heating planet. Whatever ICAO decides during its Assembly, it will never rise to the challenge of aviation’s climate problem.”

The offsetting scheme CORSIA relies on airlines paying to offset any growth in emissions above a certain baseline. After heavy lobbying by airlines during the pandemic, the ICAO changed the emission baseline – above which carbon offsets are required – from average 2019-2020 to 2019 alone. The initial baseline included 2020, a COVID-year with lower levels of flying and related emissions, whereby a lower baseline implies more emissions to offset. If the weaker 2019 baseline were to remain in place after the CORSIA pilot phase (2021-2023), as proposed by the aviation industry, the cost per passenger for flights to the US is even smaller – a mere €0. 80 in 2030.

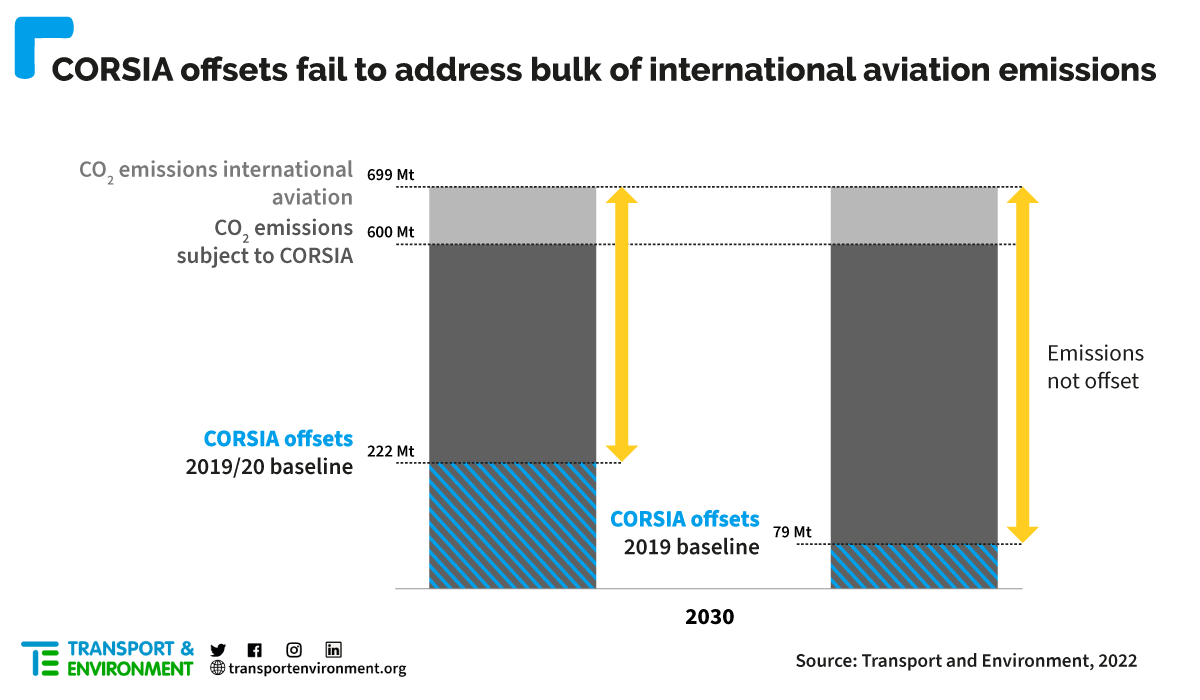

T&E and other environmental groups have for years questioned the use of offsetting as a means to reduce aircraft emissions. The study demonstrates that for all flights from the EEA to the US in 2030, CORSIA offsets – if effective – would represent a mere 8.6 million tonnes of CO2. Under current rates of predicted growth of air traffic, all flights from the EEA to the US will contribute 23.5 million tonnes of CO2 poured into the atmosphere by 2030. CORSIA offsets would cover only 36.7% of emissions at the start of the next decade. This makes it very unlikely that the industry will reach its 2050 net-zero goal, whilst also failing to address non-CO2 effects of aviation.

With a sector that has enjoyed tax exemptions and subsidies for decades, the polluter pays principle must be used to incentivise airlines to reduce their carbon footprint, T&E says. The more expensive it gets to pollute, the quicker the shift can be made towards sustainable alternatives. The EU has implemented such a mechanism with the carbon market for aviation (EU ETS), where airlines need to pay for their emissions.

However, only intra-EEA flights are currently covered by the EU ETS, whilst intercontinental flights are derogated. The study shows that if this derogation were to be lifted, on an EEA-US flight, the average added cost per passenger in 2030 would be €48.1 and €69.5 for a flight to China. For carriers operating the flights to those regions, just over 7% of operating costs would be needed for the purchase of carbon permits. After years of polluting for free, legislation must ensure airlines pay for their pollution, T&E says. These revenues can then be reinvested into sustainable solutions and cleaner fuels, like e-kerosene and green hydrogen.

“For decades now, the aviation industry has polluted without paying a dime. ICAO, along with countries like China and Russia, seem to want to prolong this status quo. The EU should not be bullied into this, and instead demonstrate climate leadership with its carbon market. The EU Parliament went as far as to propose the pricing of long-haul departing flights – which represent a large chunk of the problem”, concluded Jo Dardenne.

At its upcoming 41st General Assembly, the ICAO will also decide upon a non-binding Long Term Global Aspirational Goal (LTAG). This long-term emissions reduction goal with no enforceability mechanism is a smoke screen, says T&E. Several countries have already stated that the LTAG should not limit the growth of their aviation industry, meaning a net-zero goal is unattainable.

[1] Calculations are based on the “original scenario” whereby the baseline is 2019 for the pilot phase (2021-2023) and the 2019/2020 average for period 2024-2035. The participating countries are the 115 countries which signed up to CORSIA and 5 major aviation countries joining the mandatory phase of CORSIA from 2027 onwards. During the COVID pandemic, airlines lobbied to weaken the ambition of the scheme to include 2019 only.

[2] Calculations foresee an average cost for all passengers traveling between the EEA and the US in 2030, presuming growth of aviation emissions using a 2018 ICAO analysis, after the recovery to 2019 levels in 2025.

Watch our press briefing – joint with MEP Bas Eickhout (Greens) and Eoghain Mitchison, Public Affairs manager at easyJet.