Originally published in Euractiv

Industrial policy is back in vogue. After decades of China subsidising its battery and EV industry, now the US Inflation Reduction Act has unleashed an avalanche of subsidies and local content rules. Europe is scrambling to stay in the green tech game.

Nowhere is the global race for green tech dominance more obvious than in the competition for critical metals needed to build battery cells, renewables and power grids.

The quest for black oil has been replaced by a far more alluring palette: from silver-white lithium to chestnut colours of copper and exotic-sounding neodymium and dysprosium.

But an old-school industrial policy relying on cash handouts does not have to be the only way. Instead of a pure subsidies race, Europe should leverage its strengths and think innovatively.

Market power

Unlike Australia, Canada or Indonesia, most of Europe lacks rich mineral deposits. We are not a mining super-power. But we do have one of the world’s largest markets with strong purchasing power, which we can leverage to bring investment.

Europe’s current success in electric cars and batteries is the result of strong local demand, driven by EU clean car rules that bring investment.

As a result, the EU is projected to produce two-thirds of the battery cells our cars, trucks and grids will need in 2023. These battery powerhouses are driving investments further upstream into battery components, chemicals, metals processing and recycling.

One major piece is missing today: big rigs. Electric trucks are now entering the market, and they share the same supply chain as cars, from metals refining to component manufacturing, all the way to battery cells.

Electrifying close to half of Europe’s trucks by 2030 would add less than a fifth of the overall critical metals demand.

The battery gigafactories announced until 2030 would fully cover the needs of electric trucks, but without e-trucks, there might be a surplus – putting a business case at risk.

Look at what happened to Britishvolt, which had staff and investors but no customers.

This means ambitious clean truck rules won’t break the (metals) bank but are needed to lock in the battery investments in Europe.

Local metals potential

Potential to source some metals locally exists, provided communities are on board, and the highest environmental and social safeguards are in place.

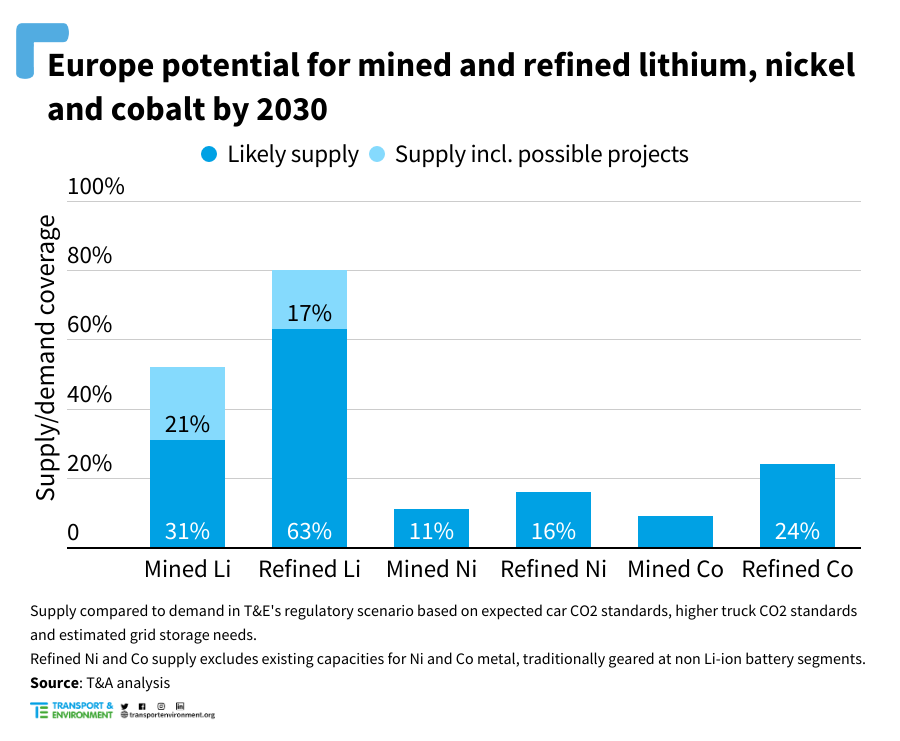

A T&E analysis of the project pipeline until 2030 shows that around 10% of Europe’s needs in cobalt and nickel can be met. For lithium – thanks in part to newer cleaner technologies such as direct extraction from geothermal brines – Europe can secure up to half its needs this decade.

Considerably more potential exists in the refining and processing stages of those metals. That’s where Europe has the industrial expertise and skills, and that’s also where most value is.

Over two-thirds of the refined lithium needed can come from local projects by 2030. Europe could also refine 16% of the required nickel by then and almost a quarter of the cobalt demand.

This is where the new Critical Raw Materials act comes in.

To lock in the potential, Europe needs to set clear goals to responsibly source and process metals, including a separate target to refine at least 50% of critical metals in Europe by 2030.

This can be achieved via strategic projects and supported with targeted funding on the strict condition that high standards are met.

Permitting should be improved. Increasing capacity and expertise in authorities that deal with applications and moving procedures online would help.

Europe can also learn from best practice elsewhere; appointing a contact point to guide companies through the process to speed things up would be a good place to start.

What’s a no-go is watering down environmental safeguards in the quest for speed. Our rules are already the bare minimum and are even due an update on mining waste. Above all, communities must be on board, and that won’t happen by shrinking the rules.

Given the global competition for resources, it’s easy to dismiss Europe’s efforts. But it’s worth remembering that today’s leader, China, does not mine many critical metals.

Europe should accelerate its partnerships with resource-rich countries too, and even co-invest in mines abroad – only guided by our high ESG standards.

When in doubt, think of recycling

Ultimately, waste is our asset. Manufacturing scrap from new battery factories spent batteries from consumer electronics and, soon, retired electric cars will account for more critical metals supply than local mining potential.

And innovation means today, we can extract what we previously considered mining waste.

One project in Sweden can supply 30% of Europe’s demand for those exotic-sounding rare earths. The Critical Raw Materials act should reward this waste-turned-asset.

New tools, not old rhetoric, are needed in Europe’s race to secure critical metals. This means thinking of waste as an asset and locking in strong climate rules, not watering down environmental safeguards.