In December 2022, EU negotiators reached an agreement on new rules for the design, production and recycling of batteries. As part of the new rules, battery manufacturers who want to sell in Europe will have to calculate and report the product’s entire carbon footprint, from mining to production to recycling. This data will then be used to establish different performance classes, and ultimately set a maximum CO2 limit for batteries coming into and produced in Europe, the idea being that producers make them using clean energy instead of fossil fuels.

While the EU has made a clear commitment to green batteries, the devil remains in the detail of how companies will calculate the carbon emissions of their batteries, including how they are allowed to account for the use of renewable energy. These details are now being worked out and will be adopted by the European Commission under a delegated act later this year. If designed well and without loopholes, the new battery carbon footprint rules will ensure that the expected massive deployment of batteries (for example in electric cars and for renewable energy storage) will be associated with minimal and decreasing overall carbon emissions.

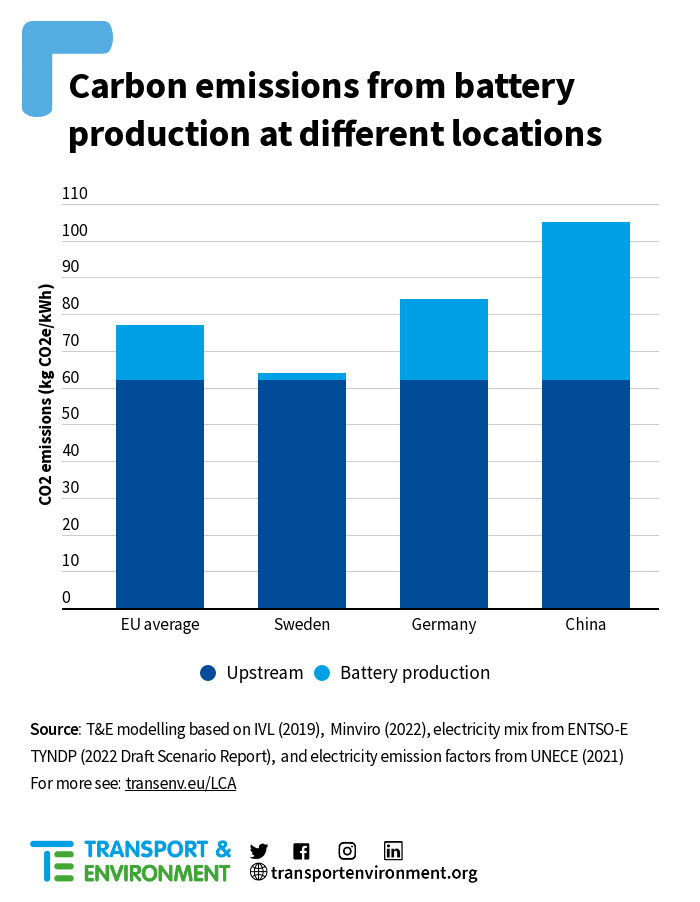

Location matters when it comes to the carbon footprint of battery production. T&E estimates that the most common lithium-ion battery (NMC-622 chemistry) produced with the EU grid in 2022 would have a 78 gCO2e/kWh carbon footprint. Producing a battery on a lower carbon grid, such as Sweden, results in a carbon footprint of 64 gCO2e/kWh, whereas the footprint increases to 85 gCO2e/kWh if produced in a higher than EU average carbon grid in Germany (in Hungary and Poland, where most batteries are produced in Europe today, the carbon footprint is 76 and 109 gCO2e/kWh respectively). Batteries produced using the average Chinese grid yield a much higher carbon footprint of 105 gCO2e/kWh (though there are regional differences). It is crucial, therefore, that new calculation and verification rules for battery carbon footprint incentivise locating battery production facilities near low carbon energy sources or bringing online new sources of renewable energy generation.

When calculating their carbon footprint, battery makers can always choose to use the average grid emissions of the country where their batteries are produced. Alternatively, they can use the plant specific values, but the rules of how to calculate these – whether based on a physical connection or some sort of contractual agreement – will be crucial to the credibility of those claims.

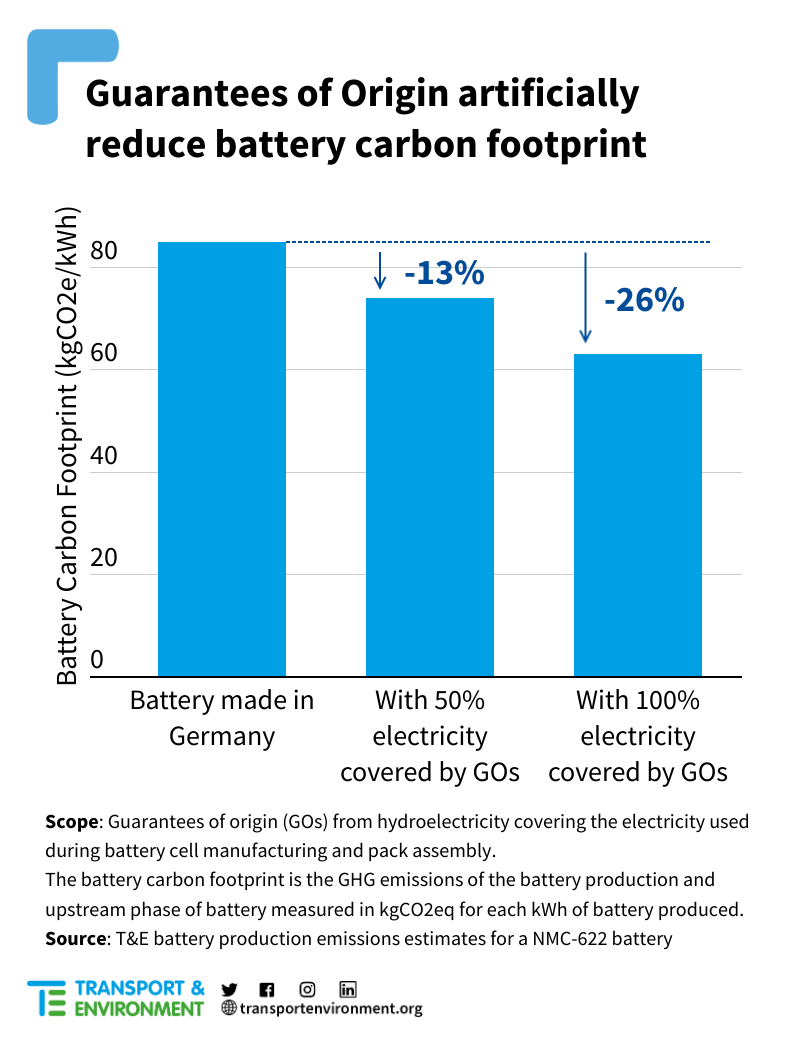

Unfortunately, the draft report by the European Commission Joint Research Centre (JRC) – responsible for preparing the draft carbon footprint rules – would allow battery makers to purchase green energy certificates throughout the entire EU market and over a 12 month period: designed specifically to allow the purchase of Guarantees of Origin (GOs). This is a problem as the current GO system does not account for real-time energy sourcing or actual energy feeds between consumption and production and therefore cannot demonstrate cleaner battery production in the real world. For example, there is significant risk that battery makers would be able to set up production in regions with a carbon intensive energy grid (e.g. Germany) and then buy their way to a low carbon footprint through cheap green certificates (e.g. solar GOs generated in Spain), instead of encouraging low carbon generation in those countries.

Furthermore, when producing batteries with renewable energy, competition with decarbonisation of the grid must be avoided, as deviating existing renewable capacity from the grid will lead to indirect emissions by bringing more fossil generators in to fill the gap. Therefore it is important that battery producers claiming green energy are bringing additional renewables onto the system. However, as the sale price of GOs is not guaranteed, and there is no direct link between the market value of GOs and the revenue required to make investments in renewable power attractive, requiring GO purchases as proof of renewability will do nothing to bring additional renewable electricity capacity to the system.

As it stands, the JRC’s draft reportwould open the door to significant greenwashing by battery makers who would be able to offset their real world emissions by reporting and claiming renewable energy use via the purchase of GOs, with no link to the real world.

T&E estimates that battery makers in Germany, for example, would be able to artificially reduce – or greenwash – their carbon footprint by up to a quarter (26%) if they use GOs to claim and report 100% of their energy consumption as renewable for the production of the battery, even if they are connected to the grid.

The only way to prevent this from happening, and reward industry front runners who are investing in new renewables generation, is to require:

- hourly matching between energy generation and use (instead of 12 months) – or at the very least over a 6 hour period – to ensure a direct connection between energy that is being sourced and consumed.

- a clear geographic link between the energy generation and use, including that the battery producing plant be located in and connected to the same bidding area (a region in which the same electricity price is applied) or adjacent interconnected bidding areas, or in the same country as the energy generating plant.

To find out more, download the position paper.