Key findings:

- The research group, Concawe, contributed to a recent industry-led push against stronger limits for European workers’ exposure to benzene.

- The effects of this toxic chemical are well established; groundbreaking studies on its harm were published as far back as the late 1970s. But the oil industry has long funded studies that contradict the overwhelming scientific consensus on the cancer risks posed by exposure to benzene and other air pollutants linked to petroleum products.

- This approach mimics disinformation tactics used by the tobacco, pesticide and oil industries in the US.

- Most recently, scientists from the European Chemicals Agency proposed more stringent benzene exposure limits, to come into effect in 2024. These were not adopted. The human cost of this decision is still unknown: but official estimates suggest that the new limits could add at least 99 additional cases of deadly cancer to the burden already borne by workers.

- Concawe did not respond to our request for comment.

60 years of ‘sound science’ for the oil industry

The ‘Conservation of Clean Air and Water in Europe’ (Concawe) sounds like any other Brussels-based environmental advocacy group. It presents itself as a not for profit organisation which aims to “conduct research programmes to provide impartial scientific information” on “environmental issues”.

Its website discloses the numerous studies the 16 million Euro budget-research centre has published since 1963 on topics ranging from the health impact of chemicals to the monitoring of emissions from cars.

Only a glimpse at it membership page reveals that it is, in fact, a division of the European Fuel Manufacturers Association, which encompasses the biggest oil companies operating in Europe. Further investigation into the group’s statutory documents shows that Concawe merged with the EU oil lobby group Europia (now Fuels Europe) in 2013 and the association’s goals now include direct support to Fuels Europe’s lobbying on EU legislation.

A deep dive into the history of Concawe casts new light on the tactics developed by the oil industry in the US and Europe for 60 yearsto tackle the growing public awareness of the health impact of its products.

In the early 60s, executives from BP and Shell were behind the inception of a new industry-wide research group on air pollution, with support from representatives of Esso and Mobil (currently operating under ExxonMobil), among others. This was partially inspired by BP’s establishment of its own internal research group.

At the time, it seemed like oil companies were willing to “(identify) possible sources of pollution” and find “ways to [… ] minimise their effects”, according to the transcript of a speech given by Pat Docksey, BP’s head of R&D Department, in 1973.

Shell and Exxon already knew a great deal about the detrimental effects of ambient air pollution in the 60s, as previous investigations, based on the disclosure of internal memos and reports, have revealed. A decade earlier, memorandums from a Shell consultant had already detailed the specific risks posed to oil industry workers heavily exposed to air pollutants such as benzene.

Docksey’s speech contains hints of what appears to be the real motive behind Concawe’s creation. It seems clear that the oil industry wanted to mitigate risks related to growing political and public awareness of pollution linked to the use of petroleum products: “There could be damage in the future and, as the use of petroleum products increased, our share of the total responsibility would increase also”. Later in his speech, Docksey also mentions discussing with Shell “problems which [was] going to face the oil industry, particularly in Europe”.

Docksey’s speech also suggests that Concawe’s creation was an attempt by the oil industry to influence the research European policy makers had at their disposal: “policy, which is primarily a matter of judgment, requires the soundest basis of technical fact that can be achieved”.

Concawe’s reporting over the years frequently refers to “sound science” in relation to policy making. This echoes the narrative used by the tobacco and pesticide industries to sow doubt about scientific evidence related the health impact of their products.

Growing consensus

Scientists have known – and written about – the risks posed by air pollutants from fossil fuels for more than 50 years.

One such risk is the inhalation of benzene by oil industry workers. The chemical was for many years used in a range of industries as a solvent. Today its sale is heavily regulated in many countries, including those in the EU. However, it remains a component of crude oil and gasoline, meaning that workers in oil extraction, refining, and distribution are still being exposed to its harmful effects. And the risks extend beyond those directly in the industry: emissions from gasoline service stations, vehicle exhausts and industrial activity mean the general population is also in harm’s way, as shown by the following evidence.

The first cases of cancer linked to benzene were reported as early as 1928.

In 1977, the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) conducted a landmark study on benzene exposure to workers involved in Pliofilm manufacture. Workers occupationally exposed to benzene in 1940-49 were followed for vital status up to 1975. It found evidence that the exposure increased participants’ risk of developing leukaemia. This led to the issuance of the first US standard on benzene occupational exposure in 1978, though this was not enforced until 1987. In 2006, the US Environmental Protection Agency stated in a report that “benzene is the most significant contributor to cancer risks from all outdoor air toxics” and limited the chemical’s concentration levels in fuel.

In the 90s, academic studies documenting health issues linked to the inhalation of ambient air pollutants started to accumulate. This led to an important 1995 study published by the US American Cancer Society that found an association between air pollution from particulate matter and lung cancer.

Around the same time, and stretching into the mid-2000s, concerns about particulate matter from diesel exhausts grew. Several studies published in 2012 established that workers exposed to diesel exhaust fumes had an increased risk of developing lung cancer. One of the most notable research project was carried out on miners by the US National Cancer Institute (NCI) and NIOSH in 2012; another was conducted on workers in the trucking industry and published in 2008.

Bert Brunekreef, Emeritus Professor of Environmental Epidemiology at the University of Utrecht, told Transport & Environment (T&E) in an interview that those studies generated an “enormous amount of discussions on what needed to be done about long term exposure to particulate matter”.

In response to growing evidence that the use of fossil fuels was linked to cancer risks, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) launched several scientific reviews. The agency is a branch of the World Health Organization; its monographs form the basis of the most authoritative worldwide resource to identify cancer-causing substances. IARC monographs are not legally binding. They are, however, viewed globally as authoritative and are frequently used to update governmental classifications and regulations that protect people’s health. For instance, its new classification of glyphosate in the mid-2010s has triggered an intensive debate on the authorisation of pesticide use in the EU. Peter Infante, an epidemiologist and a former director of the office that reviews health standards at the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration, said in an interview that the IARC hosts the ‘best programme in the world to identify carcinogens’.

The agency classified benzene as a “carcinogenic to humans” pollutant in 1979, on the basis that it caused leukaemia. It also classified diesel exhaust as “probably carcinogenic” in 1989.

Then, in the 2010s, it announced its intention to launch a review of its classification of diesel emissions and to conduct its first-ever review on outdoor air pollution.

This must have immediately worried the oil industry.

Casting doubt

In the 2010s, the IARC launched two scientific reviews on the carcinogenicity of diesel exhaust and ambient air pollution. It wanted to understand whether there was sufficient evidence to raise its classification from “probably carcinogenic to humans” to “carcinogenic to humans” – the highest category in the institution’s ranking.

Documents, an analysis of academic studies’ funding disclosure, as well as interviews with academics from inside and outside the IARC, suggest that Concawe participated in an industry campaign to influence the review and block the strengthening of the classification.

The oil industry-backed research group secured observer status for meetings of the 24 independent academics who formed the working group tasked by the IARC with reviewing and voting on the solidity of the scientific evidence.

In June 2012, a consultant named John Gamble – a former epidemiologist for Exxon – attended the IARC working group meetings on the carcinogenicity of diesel exhaust on, among others, Concawe’s behalf. Indeed, he was representing a coalition of several industries, gathered under the umbrella of the “IARC review stakeholder group”, which included Concawe as well as the US oil industry lobby association (American Petroleum Institute), other European and US trade associations representing the automotive sector such as ACEA (European Automobile Manufacturers Association), and the US EMA (Truck and Engine Manufacturers of America). Moreover, John Gamble disclosed receiving “significant research funding” from Concawe to the IARC at the time.

One way that Concawe appears to have tried to influence the IARC’s review was to fund him and other consultants to publish critical reviews of the literature in scientific journals prior to the working group’s meetings.

In 2010, John Gamble published his first critical review on the evidence of carcinogenicity of diesel exhaust in what several independent academics consider to be an industry-friendly academic journal. The review concluded that “support(ing) a traditional diesel exhaust–lungcancer hypothesis requires more studies”. The author disclosed that the study received financial support from Concawe.

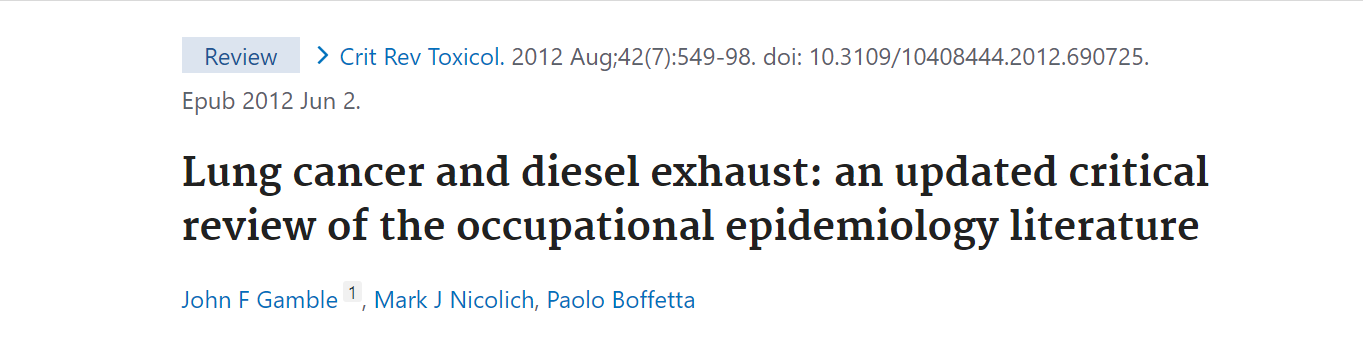

Then, a few days prior to attending the IARC working group meetings as an industry observer, John Gamble published another literature review in which he highlighted limitations in several prominent academic studies on the link between lung cancer and diesel exhaust, including the 2012 US NCI/NIOSH study on miners. The paper, published in the same previously referenced industry-friendly journal, states that “the weight of evidence is considered inadequate to confirm the diesel-lung cancer hypothesis”.

The article’s conflict of interest section disclosed that both John Gamble and another co-author received financial support from Concawe for their work on the review. They were also both formerly employed by ExxonMobil. Another co-author, a well-known university professor and former IARC director named Paolo Boffetta, disclosed funding from the Mining Awareness Resource Group (MARG), which is a lobby group representing the mining industry in the US.

According to a scientist within the IARC monograph programme at the time, John Gamble raised the same criticisms regarding studies showing association between lung cancer and diesel exhaust during the IARC working group meetings.

These objections were in vain: in June 2012 the IARC working group established that there was “sufficient evidence” for the carcinogenicity of diesel-engine exhaust and strengthened its classification of the substance as “carcinogenic to humans”. Commenting on the claims from the literature reviews sponsored by the oil industry, a scientist within the IARC monograph programme told T&E: “Each study’s limitations are considered carefully by the working group” but that “the totality of evidence showed there was sufficient evidence that diesel exhaust was carcinogenic to humans”. According to him, the pieces of research decried by the oil industry-backed coalition were among “the most informative” studies in guiding the working group’s decision.

George Thurston, Professor of Medicine and Population Health at the NYU School of Medicine, also considers that further academic work has shown since 2012 how ‘robust’ the NCI/NIOSH miners studies actually were, despite critiques by Gamble & al. He considers the literature review sponsored by the oil industry to be‘ an outdated and incomplete review of the state of knowledge on the diesel exhaust literature’.

In response to our questions, Paolo Boffetta stated that they “interpreted some critical pieces of the epidemiologic evidence on the association between diesel exhaust and lung cancer in a different way compared to the IARC Expert Group”. He denies that“MARG and other companies had (a) role in any aspect of the research”and considers that“good-faith disagreement is a key component in the advancement of science”.

Mr Gamble did not respond to our request for comment.

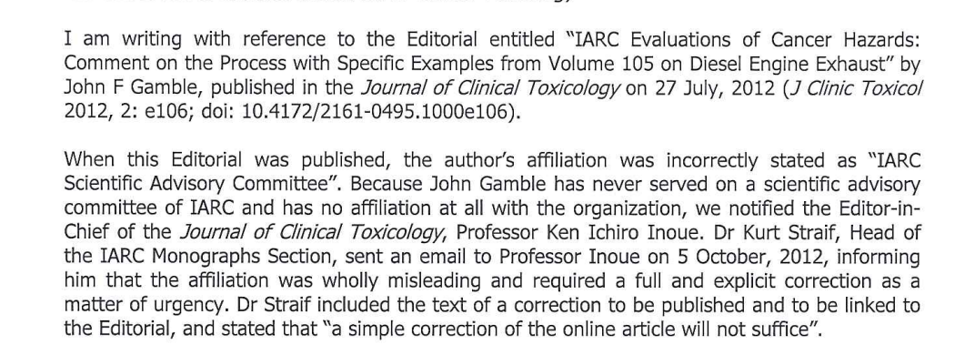

Nevertheless, critiques of the robustness of the association between lung cancer and diesel exhaust did not stop after the IARC published its new classification. In July 2012, John Gamble published a fierce critique of the IARC monograph in the form of an editorial published in the Journal of Clinical Toxicology, stating that: “Sometimes IARC conclusions that are based on epidemiology have been controversial, if not mistaken or misinterpreted”. He also insisted that “The recent IARC conclusion on diesel engine exhaust is likely to be controversial as it is based on potentially incorrect interpretations of major studies because of limitations in the scientific assessment”.

The editorial also outlined several proposed modifications to the monograph governance regarding conflict of interest with industry, highlighting how ‘opinions should be judged on factual accuracy and logic rather than source’ and that ‘closed process that does not encourage open scientific debate or alternative viewpoints’. He later goes on, calling for ‘everybody’ to be able to ‘provide comments to the final draft monographs’, a privilege which he did not hold when he was an industry observer. Other industries, such as the American Chemistry Council, also later attempted to amend IARC conflict of interest rules to allow more room for observers.

The IARC did not modify its guidelines related to industry observers’ roles, which state that they can provide comments during meetings but can’t participate in the drafting and voting process of the scientific review.

Letters sent by the IARC to the editor of the scientific journal which published John Gamble’s editorial accessed by T&E also show that the WHO Cancer Agency referred to “numerous errors of facts” made by the author in his editorial, “which [it] refrain[ed] from detailing”.

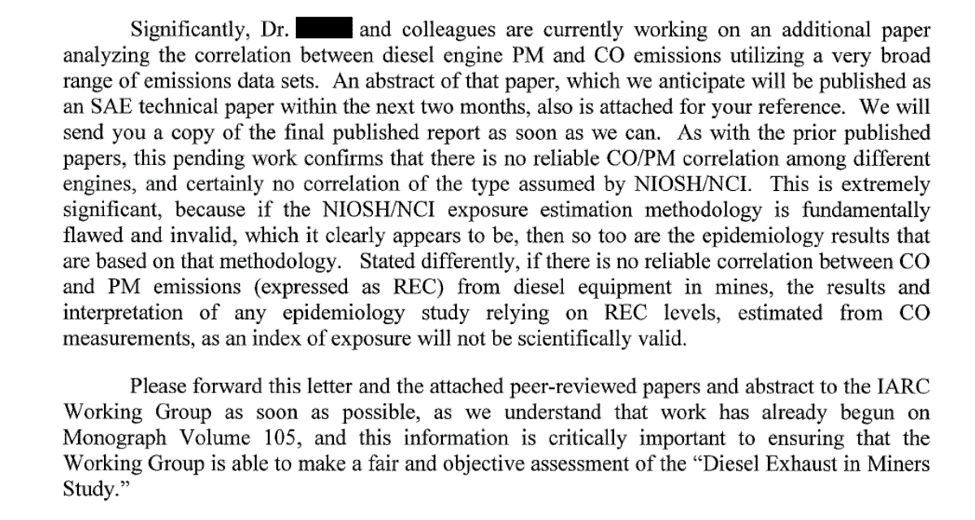

Documents accessed by T&E also suggest that another member of the industry coalition represented by John Gamble tried to influence the working group’s evaluation. In a letter sent to the IARC in January 2012, the Truck and Engine Manufacturers of America (EMA) lobby group highlighted what it called ‘a major flaw in the key assumption’ in an exposure study done as part of the same research project conducted by the US NCI/NIOSH on Miners about exposure to diesel exhaust -which was also criticized by the consultants funded by Concawe- contending that they would not be “scientifically valid”. The letter also included references to several already-published papers, as well as some that were soon to be published by “colleagues” within the trucking industry, requesting the IARC to share them with the working group.

This attempt was unsuccessful and did not prevent the IARC from strengthening its classification of the carcinogenicity of diesel-engine exhaust either in June 2012 .

Subsequently, in 2013, another IARC working group unanimously classified outdoor air pollution and particulate matter from outdoor air pollution as “carcinogenic to humans”.

This time, five years later, in 2018, Concawe published a report on its website rebutting the review.

This was prepared by three other consultants, who were sent as observers on Concawe’s behalf at the time of the IARC monograph preparation, and subsequently concluded that “better studies are needed to provide a more helpful conclusion for understanding risk than the IARC evaluation that PM [Particulate Matter] is carcinogenic to humans.”This assessment was based on a review of “the strengths and limitations” of the scientific literature on air pollution and cancer highlighting that confounding factors such as smoking may have affected the results.

Ebba Malmqvist, Associate Professor in the Division of Occupational and Environmental Medicine at Lund University, said in an interview that those allegations were unfounded: “All studies have flaws and it is the weight of evidence that matters – that you see similar results in each study.”

On Concawe’s 2018 review, Malmqvist says the organisation “ignored the sum of evidence on the carcinogenicity of air pollution”.

She and other scientists told T&E that industry-sponsored research was used strategically to delay regulators by suggesting that uncertainty remained in the science about oil products’ carcinogenicity. The suggestion was that this uncertainty meant regulatory measures to protect people’s health did not need to be upheld.

Despite not succeeding in undermining the 2012 and 2013 IARC monographs, it appears that Concawe has continued to use the same modus operandi more recently to prevent EU regulators from increasing workers’ protection against the cancer risks posed by benzene.

Concawe vs the EU

The industrial use of benzene has decreased worldwide and in the EU since its carcinogenic properties became widely publicised. Sales, the level of concentration in fuel, and ambient and occupational exposure have all been regulated.

As a result, both outdoor air concentrations and occupational exposure levels have declined significantly in Europe since the year 2000. However, it remains an ubiquitous pollutant which is present in, among others, the petroleum and refining industries, as well as in the distribution of petroleum products.

Six years ago, the EU laid the groundwork for the revision of benzene occupational limits, in a bid to strengthen protection for workers. At the time and up until now, industries had to comply with an average exposure limit of 1 parts per million (ppm), roughly around the same levels proposed in the US following the release of the 1977 NIOSH study and which have been implemented since 1987.

Documents show that Concawe authored and funded several studies to support an active behind the scenes lobbying campaign against the EU’s proposed limit revisions.

E-mails exchanges and documents accessed by T&E show that Concawe first tried to influence the scientific review done by the Risk Assessment Committee (RAC) of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), in support of the drafting of a proposal for new occupational limits, based on the latest scientific evidence.

In an email sent to ECHA in June 2017, Concawe refers to a research project it launched to perform a “reanalysis of data” aimed at “addressing the ongoing low dose benzene debate”. By that time a range of academic studies by independent researchers had shown an increased risk of benzene exposure at lower average exposure limits than the ones currently in place in the EU and the US; that is, below 1 ppm. Most notably, the US National Cancer Institute reported increased risks of leukaemia around an average 1 ppm exposure level in 1997, and at lower than an average 1 ppm exposure levels in 2004. Those findings were confirmed by studies done in the EU on Norwegian workers in 2008 and 2015. Studies had also shown that the risks posed at very low levels of exposure may have been underestimated due to the way benzene metabolises. The potential underestimation of risks at low exposure levels was recognised in a ruling from the US Environmental Protection Agency in 2007.

The outcome of the research project commissioned by Concawe and referred to by email sent to the ECHA, would on the contrary, clearly undermine all of the above findings.

Authors of the research papers and opinion paper referred to in the email, and published in the Journal of Chemico-Biological Interactions, included Concawe executives and consultants from research firms Cox Associates and the UK Health & Safety Laboratory, which both received funding from the oil industry, directly or in support of research projects. Their conclusions, based on a reanalysis of a 2008 study authored by Dr Stephen M. Rappaport, an Emeritus Professor of Environmental Health at Berkeley on benzene metabolism concluded that there was no “increased hazard from benzene at decreased exposure levels”. Another study funded by Concawe on benzene in 2012 supported the claim that “existing regulatory standards for benzene, such as occupational exposure limits, are already sufficient to protect worker health for benzene-related leukaemias”, according to the group’s own reporting.

Rappaport told T&E those conclusions were flawed, saying they were based on “an exclusion of critical data which made it impossible for them to observe the low-dose behaviour”.

Concawe was echoing a much earlier stance on the subject of benzene exposure, according to Peter Infante, the former director of the office that reviews health standards at the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration who authored the groundbreaking 1977 US study referred to earlier in this investigation.

Infante says: “After 1977, the industry argued that benzene caused leukaemia but at high exposure levels only. They paid consultants to produce risk assessments that would show much lower risks of leukaemia at low benzene exposure levels. This was so government regulatory agencies would not lower exposure levels mostly in the general environment.”

Concawe’s article was referenced in the literature review that the ECHA included in its 2017 proposal. But it failed to influence the recommendation: the ECHA suggested that the EU implement an average 0.1 ppm limit. In March 2018, the ECHA’s RAC suggested a 0.05ppm limit, based on a review of the scientific literature.

Concawe objected vehemently to the proposed limits. In a letter sent in November 2017 to the ECHA’s RAC chairman, it “express(ed) concerns” about “the proposal to lower the occupational exposure limit for benzene”, highlighting “new scientific evidence, shared with RAC OEL working group, does not support the value proposed by RAC which we consider to be overly conservative and scientifically unjustified”.

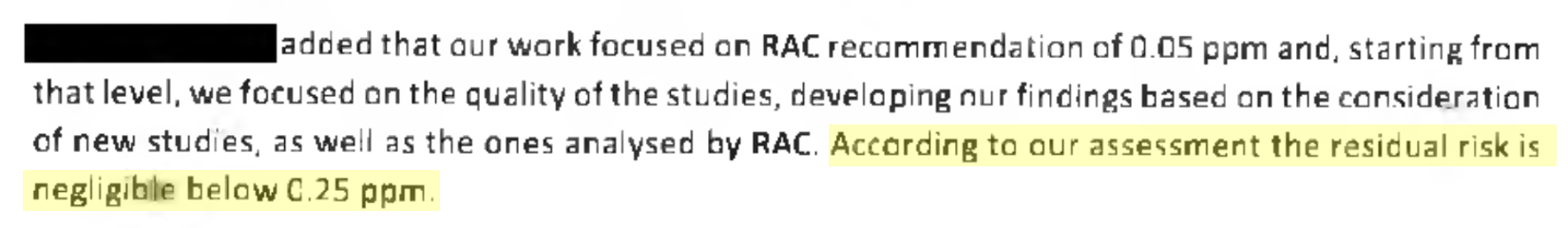

In the minutes of an April 2019 meeting between Concawe and representatives from the Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, a body of the European Commission in charge of drafting legislative proposals related to workers, Concawe refers to an analysis of the “quality of the studies” used by the RAC, suggesting a “residual risk negligible below 0.25 ppm” for workers and “supporting an Occupational Exposure Limit of 0.5 ppm” – about 10 times higher than the RAC’s proposed limit.

T&E has accessed position papers prepared by Fuels Europe, Concawe, and Petrochemicals Europe (Cefic) in March 2019 which show that those exposure levels were put forward as the industry’s preferred limit. The paper advocates for a 0.5ppm limit in the short term (three years) and a 0.25 ppm limit thereafter.

According to Peter Infante, the industry assessment of “safe exposure” levels is misleading: “Studies have shown significant risks of cancer below that level”. Going further, he and other academics consider that “There are no safe exposure levels for benzene for workers.” This is in line with the industry’s own position in 1948, when the American Petroleum Institution concluded that “the only safe concentration for benzene is zero”. The Risk Assessment Committee of the ECHA, on the other hand, suggested in 2018 that an average exposure level of 0.05 ppm ‘can be considered to be associated with no significant residual cancer risk”.

Ultimately, in 2022 EU institutions agreed on a final regulatory threshold not too far from the industry position, setting up an interim target of 0.5 ppm from April 2024 to 2026 and a final target of 0.2 ppm thereafter. These numbers were based on a proposal agreed on unanimously by a tripartite body composed of trade unions, representatives of the industry, and EU member states. Sources close to the file say that Business Europe, the European pan-industry lobby group, was formally representing employer organisations within the tripartite body, which however encompassed other industry bodies including a consultant close to the petroleum and chemical industry.

According to Dr Tony Musu, who represented the trade union ETUI at the meetings “the adopted limits were a compromise between the health benefits and the cost to the industry”. This is confirmed by extracts from an impact assessment done by the European Commission that states: “Option 3 [0.2 ppm] has been considered as the most balanced option between adequate protection of workers at the EU level and prevention of closure and other severe disadvantages for the industries.”

According to estimates from the same report, at least 99 additional cases of leukemias and 79 additional deaths are likely to happen in the next 60 years because of the discrepancy between the adopted limits and the ones proposed by ECHA’ scientific committee. Tighter limits would have only entailed a cost equivalent to 0.17% of the industry turnover, according to the same document.

Average exposure levels at workplaces in Europe remain below 0.1ppm, according to official estimates. However, they differ widely amongst sectors and highly depend on specific tasks performed. High exposure levels have been reported notably during maintenance work in refineries or at gasoline pump and during tank cleaning work in the petroleum industry.

The true human cost of not following scientific recommendations for benzene is, however, hard to establish with certainty. Extracts of a consultant report done in preparation for the European Commission impact assessment and accessed by T&E recognised that the estimate of leukaemia cases and thus the health benefits due to lower limits may have been “underestimated”. The report quotes other estimates provided by a report done by trade union ETUI, as well as another commissioned by insurance companies, which showed an increase of the number of leukaemia cases by a factor of 6 and 10 respectively. According to a source within the European Parliament close to the political negotiations on the new regulation at the time, “Impact assessments done by the European Commission tend to be pro-business and quite conservative from a health point of view.”

Concawe did not respond to our request for comment.

Today, one million workers remain exposed to benzene in Europe. As Peter Infante puts it: “Workers are currently not sufficiently protected against benzene’s risks by any government standards.”

Notes

T&E used a mix of standard investigative research practices for performing the investigation: notably desk research, access to documents through freedom of information requests, and interviews with several sources. All information presented in the investigative report has been thoroughly referenced, through use of quotes, footnotes and presentation of extracts of documents when not available in the public domain for full references, see PDF version.