Interested in this kind of news?

Receive them directly in your inbox. Delivered once a week.

Jos Dings, executive director of Transport & Environment, said:“The European Commission has finally revealed that Europe’s policy failure in stimulating bad biofuels is even more spectacular than previous scientific research indicated. We should phase out the mandating, subsidising and zero-carbon accounting of these fuels at European and national level after 2020.”

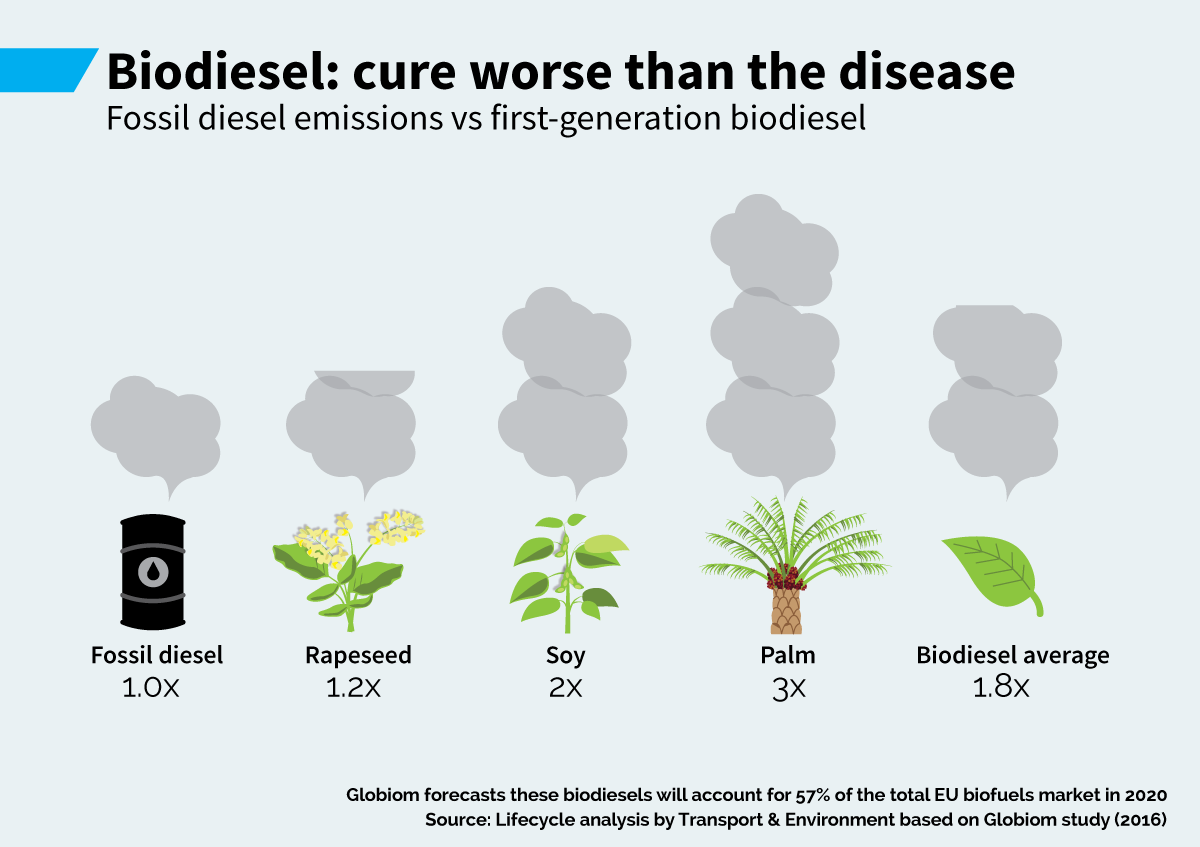

The long-delayed EU study found palm, rapeseed and soy-based biodiesel to have land-use change emissions – which occur when new or existing cropland is used for biofuel feedstock production – that alone exceed the full lifecycle emissions of fossil diesel. T&E’s analysis adds to these figures the direct emissions of biofuels e.g. from tractors, fertilisers, and the installations, and subtracts emissions from the fossil alternative.

It finds that on average, biodiesel from virgin vegetable oil leads to around 80% higher emissions than the fossil diesel it replaces. For instance, soy and palm-based biodiesel are even two and three times worse respectively. These biodiesels are the most popular biofuel in the European market and have been forecasted to have an almost 59% share in 2020.

In total more than three-quarters of biofuels, which includes bioethanol as well as biodiesel, are forecast to have lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions similar or higher than fossil petrol and diesel in 2020.

Jos Dings concluded: “The cure is plainly worse than the disease. The 7% cap on food-based biofuels has helped though, and should be lowered to zero after 2020. These fuels should also not count as zero-emission fuels. If we do not end incentives for bad biofuels, the better ones will not stand a chance.”

Last year’s reform of EU biofuels policy established a limit on the growing consumption of land-based biofuels, which, because of indirect land-use change (ILUC) emissions, often increase carbon emissions rather than reducing them. But the reform failed to include ILUC emissions in the carbon accounting of biofuels under the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and Fuel Quality Directive, meaning harmful biofuels can still be counted toward the EU targets and receive public financial support.

The European Commission is currently reviewing the RED and sustainability criteria for all bioenergy including biofuels, and it will publish a proposal in the final quarter of this year.